From Book to Collectible: The Evolution of Alice in Wonderland

When Lewis Carroll published Alice in Wonderland in 1865, he probably did not imagine that its story would inspire a universe of interpretations and adaptations that cross eras and mediums. His story was not just a children's fairy tale, but a symbolic journey, full of surreal characters that have fascinated generations of readers, artists and filmmakers. This fascination has turned over time into a cultural phenomenon that has found expression in marketing and collecting. In the '30s, when cinema was experiencing one of its most significant evolutions with the transition from silent to sound, the world of Alice returned to the fore with new forms of diffusion:

In 1930, Carreras Ltd. published the Black Cat Game of Alice in Wonderland, a collectible game that turned Carroll's characters into cards to trade and collect.

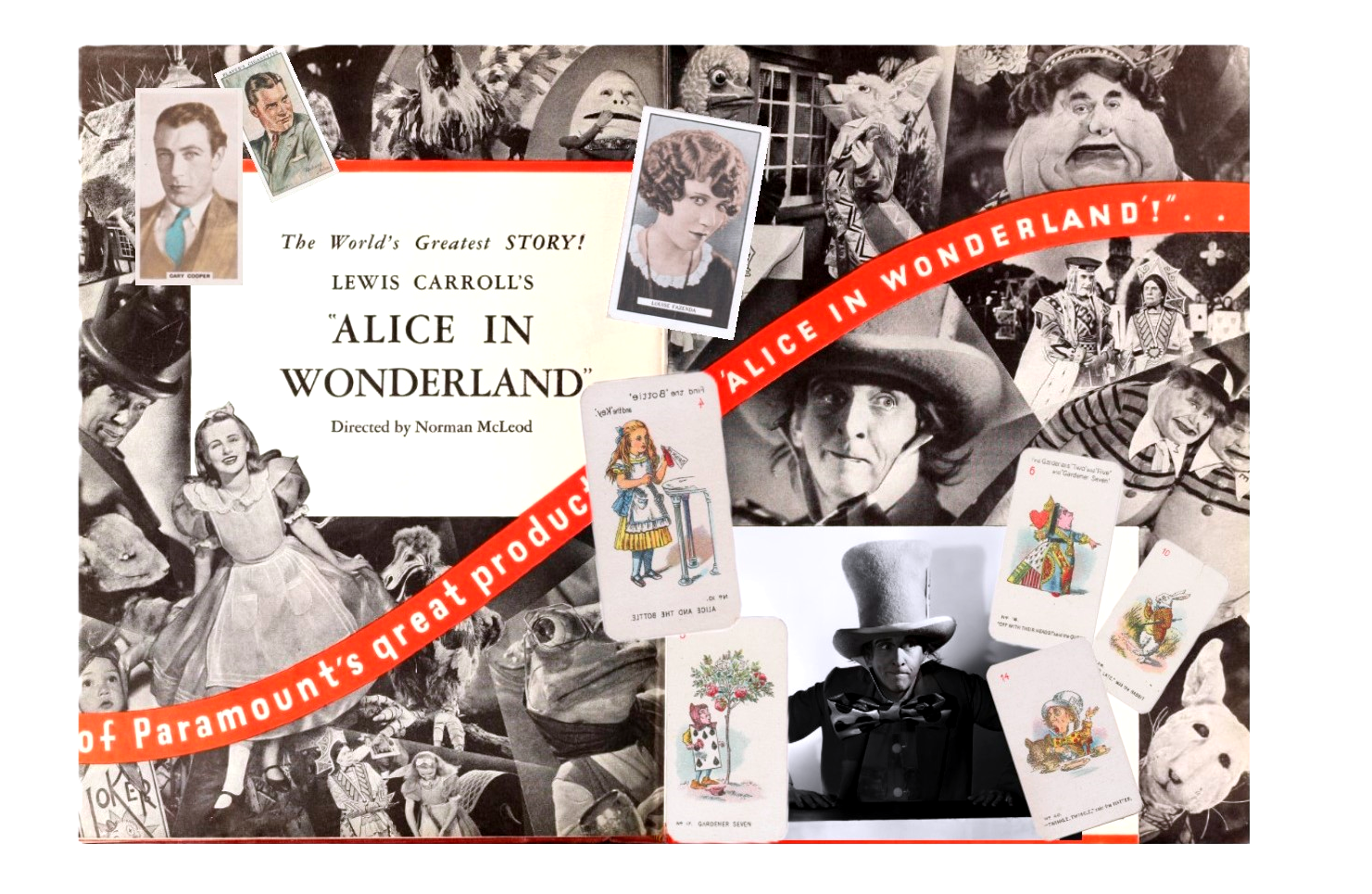

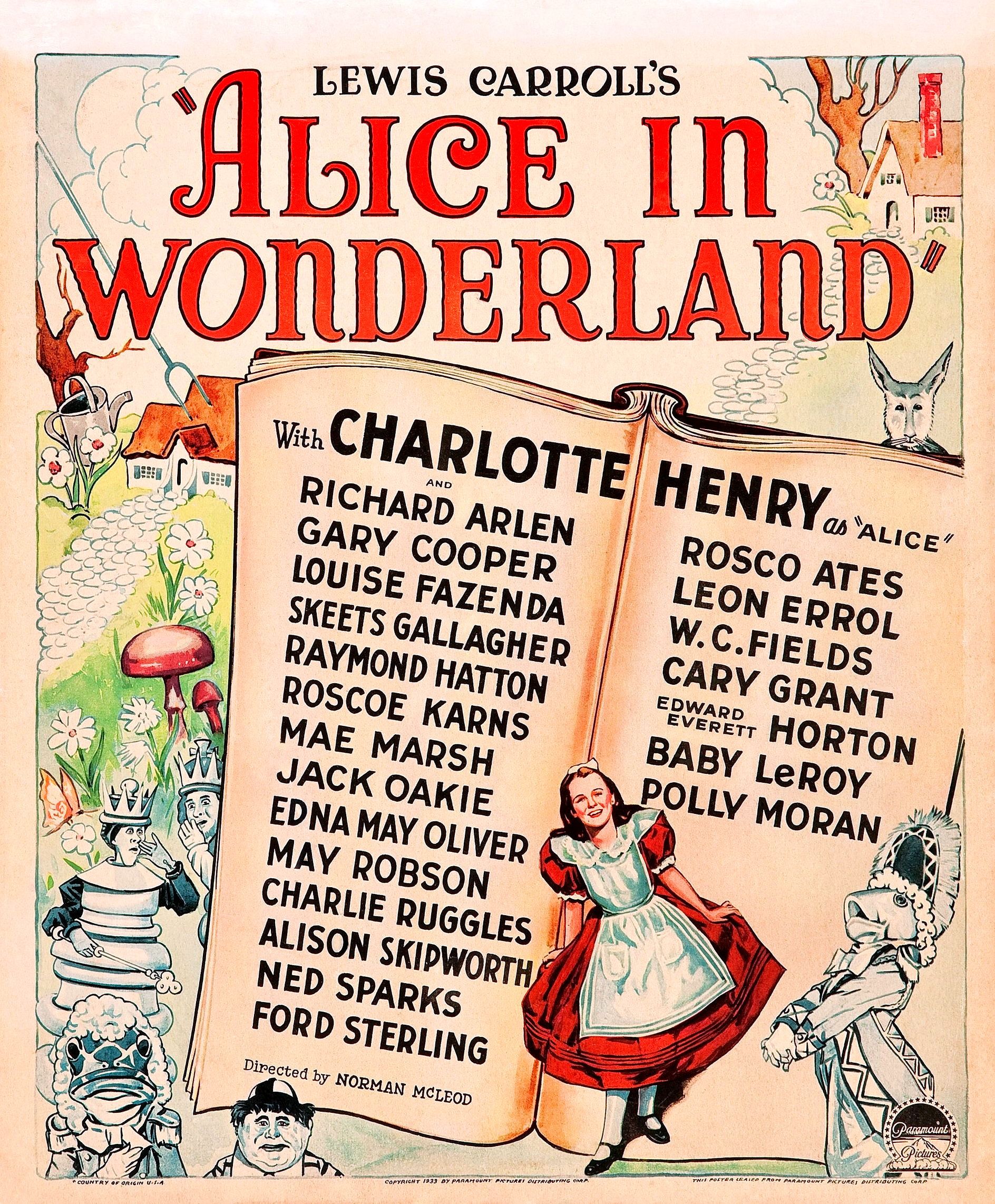

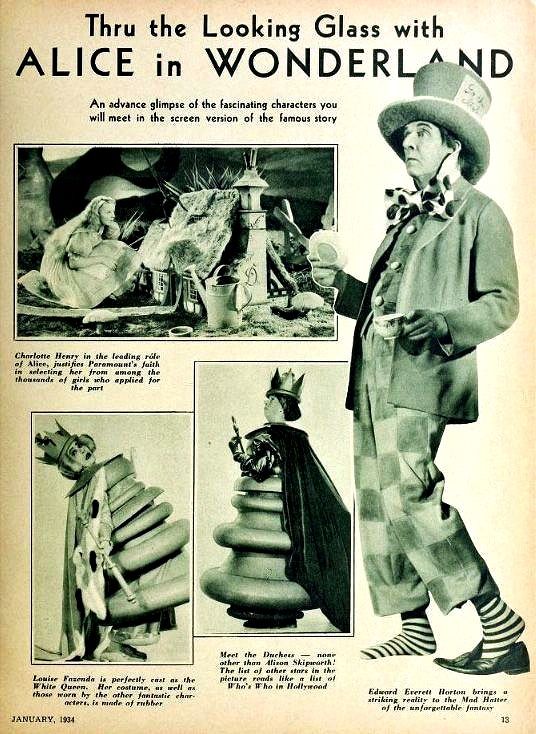

In 1933, Hollywood presented a new film adaptation of the story, with Charlotte Henry in the role of Alice and famous actors such as Cary Grant and Edward Everett Horton as the bizarre creatures of Wonderland.

Through these interpretations we can see how Alice's world has moved from the pages of a book to the culture of collecting, testifying to the way in which the marketing of the period took inspiration from literary works to create new forms of entertainment. Following the thread of the narrative, we can connect the characters of the 1933 film to trading cards, a journey through literature, cinema and memorabilia to rediscover a piece of history through collecting.

At the dawn of cinema

Alice in Wonderland and its first visual experiments

In 1903, just 37 years after the publication of Lewis Carroll's novel, British cinema made the first film adaptation of Alice in Wonderland. Directed by Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow, this 8-minute silent short film represented a pioneering experiment in fantasy cinema, trying to translate Alice's surreal world into images.Despite the rudimentary means of the time, the film tried to recreate the magic of the book through innovative special effects for the time:

Reduction and enlargement of Alice, to simulate her magical transformations.

Hand-painted sets, which evoked the fairytale atmosphere of the novel.

Theatrical movements of the actors, which compensated for the lack of dialogue and helped to make the film more expressive.

This first version showed how much the story was already rooted in the collective imagination, so much so that it became one of the first film subjects in history. Although many parts of the film have been lost, a version restored by the British Film Institute allows us to rediscover this rare testimony of early cinema. The success of Alice in Wonderland in the world of cinema did not stop at this first transposition. Its popularity continued to grow, leading to new silent versions that preceded the advent of sound.

The first American version of Alice in Wonderland

In 1915, director W.W. Young made the first American film adaptation of the story of Alice in Wonderland. This film, longer than previous versions (about 52 minutes), stood out for its more structured approach to storytelling and its willingness to integrate elements of Through the Looking Glass into the plot. Unlike the 1903 short film, this version could boast a more ambitious direction and a visual representation that tried to respect John Tenniel's original illustrations, much loved by readers of the time. The sets and costumes took up the style of the novel, helping to maintain a direct link with the literary material. Despite technical progress, the 1915 film remained silent, with strongly theatrical acting, typical of the time. Without the aid of sound, the actors used marked movements and exaggerated expressions to make the scenes understandable. This version was important because it solidified the American public's interest in Alice in Wonderland, contributing to the growing popularity of the story in the following decades.

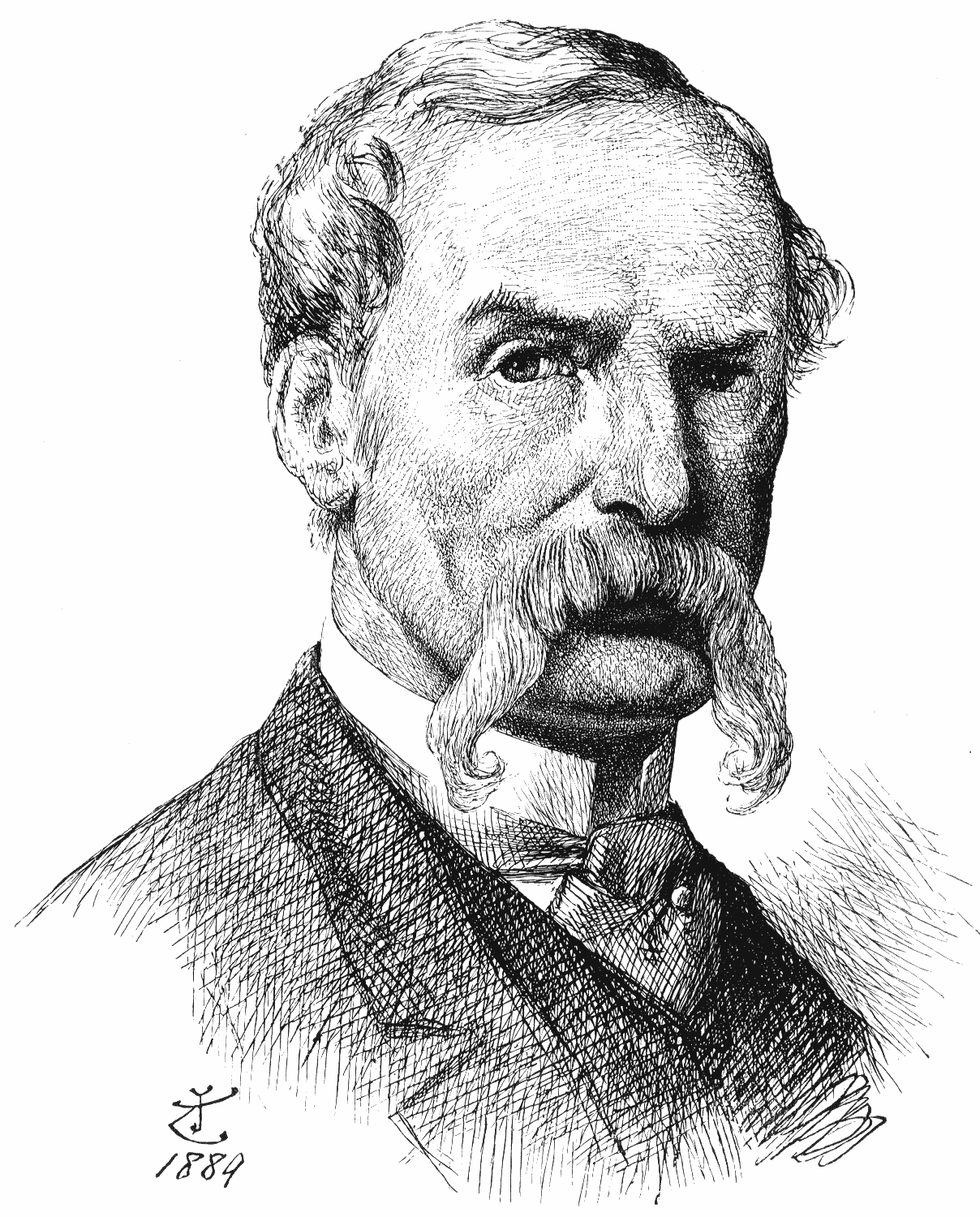

John Tenniel

Self-portrait John Tenniel - Wikipedia

Illustrator and Caricaturist of Alice in Wonderland

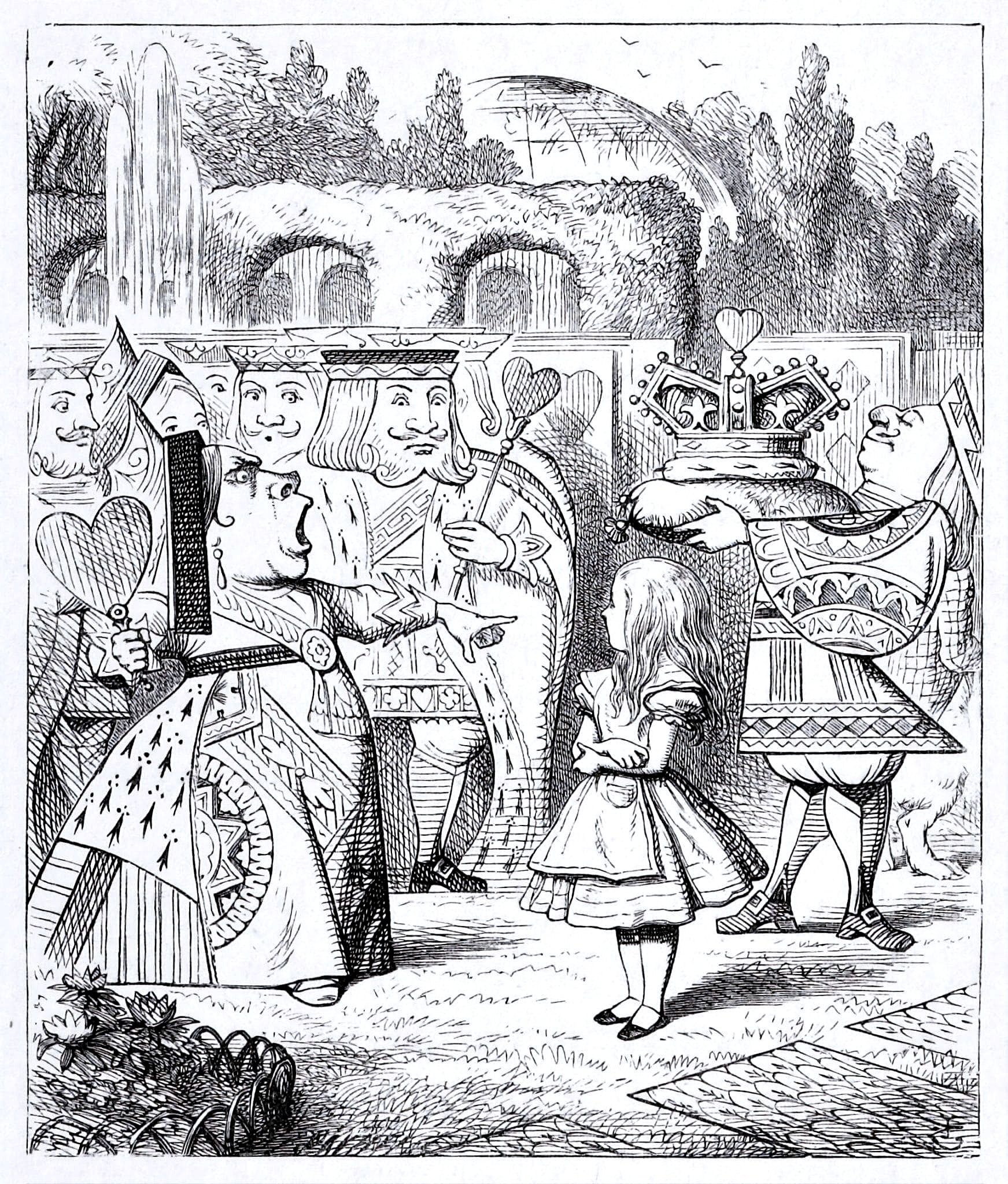

John Tenniel was a prominent British illustrator and caricaturist, best known for his work on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). His illustrations have defined the aesthetics of the characters and settings, profoundly influencing subsequent artistic and cinematic interpretations. In addition to this iconic collaboration, Tenniel had a major career as a political cartoonist on Punch, contributing to the social and political satire of the Victorian era.

Born on February 28, 1820 in Bayswater, London, Tenniel was the son of John Baptist Tenniel, a fencing and dance master, and Eliza Maria Tenniel. Raised in a modest environment in Kensington, he received a limited education, learning fencing, dancing and horse riding from his father. However, his life took a dramatic turn when, at the age of 20, he lost sight in his right eye due to a fencing accident. Tenniel hid the injury from his father so as not to upset him and continued to pursue his passion for art. After a brief period of study at the Royal Academy, Tenniel decided to embark on a self-taught path, exhibiting his first painting at the Society of British Artists at the age of 16.

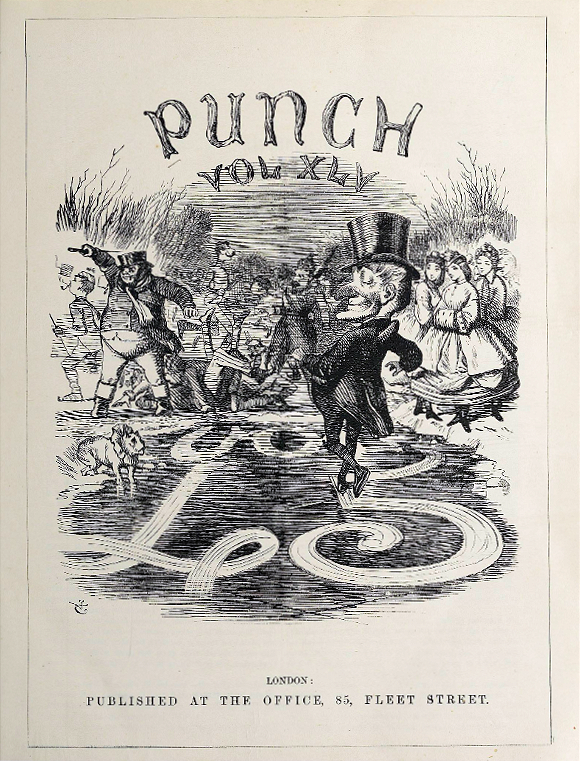

Punch - July 1863

In 1850, Tenniel joined the satirical magazine Punch, initially working alongside John Leech as a cartoonist. Upon Leech's death in 1864, Tenniel became the magazine's chief caricaturist, a role he held until his retirement in 1901. During this time, Tenniel produced over 2,000 caricatures, tackling themes such as working-class radicalism, war, economics and politics, helping to shape Victorian public opinion. His cartoons stood out for their artistic accuracy and incisive commentary, profoundly influencing the way society perceived political and social issues.

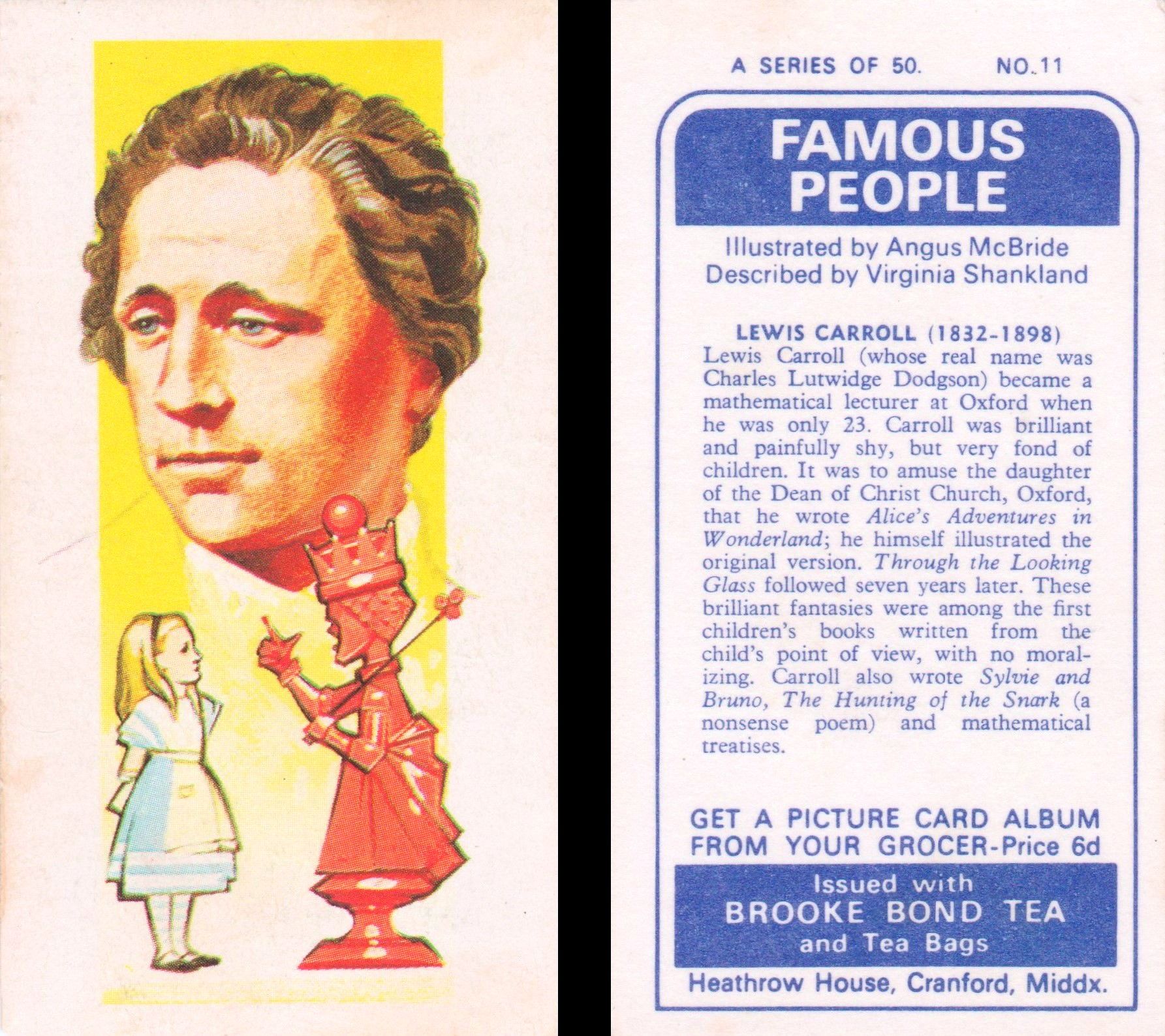

Card n.11 - FAMOUS PEOPLE - BROOKE BOND TEA (1969)

(personal collection)

In 1864, Lewis Carroll chose Tenniel to illustrate Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Carroll initially tried to make the drawings himself, but dissatisfied with his skills, he decided to rely on a professional illustrator. Orlando Jewitt, a prominent engraver, recommended Tenniel, already known for his work on Punch. Their collaboration, however, was not always harmonious. Carroll was extremely meticulous, providing detailed instructions, but Tenniel had a strong and independent artistic vision. In fact, Carroll initially approved only one draft: that of Humpty Dumpty, leading to numerous exchanges and revisions before arriving at the final illustrations. Another difficulty was the print quality of the first edition in 1865. Tenniel was dissatisfied with the result and Carroll, in order to guarantee an excellent product, decided to withdraw the entire print run and reprint it with a higher quality. Despite the difficulties, the result was exceptional. Tenniel also illustrated Through the Looking-Glass in 1871, creating images that are now considered literary icons, influencing later editions and film, theater, and art adaptations. His work on Punch helped elevate the status of cartoonists and illustrators, transforming a profession considered amateur into a respected and influential one. In 1893, Tenniel was knighted, becoming the first illustrator to receive the honor. In addition to film and stage adaptations, the visual influence of Tenniel's illustrations has also reached the world of collecting.

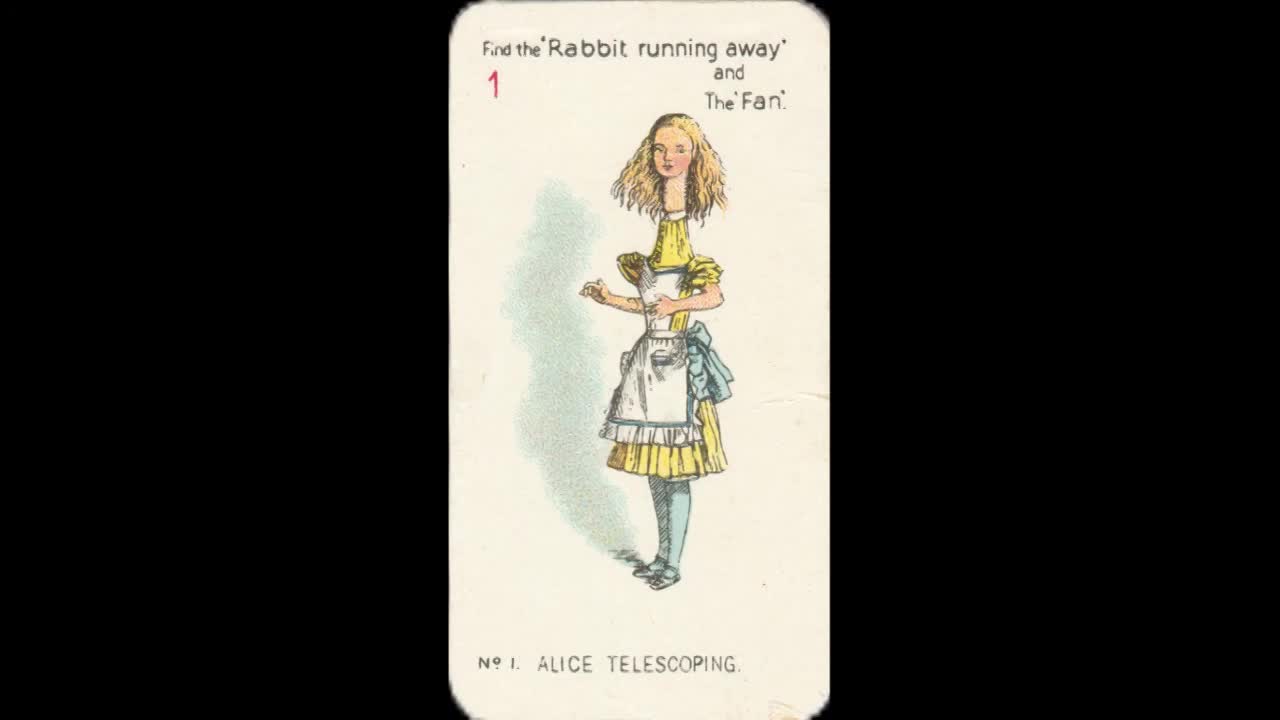

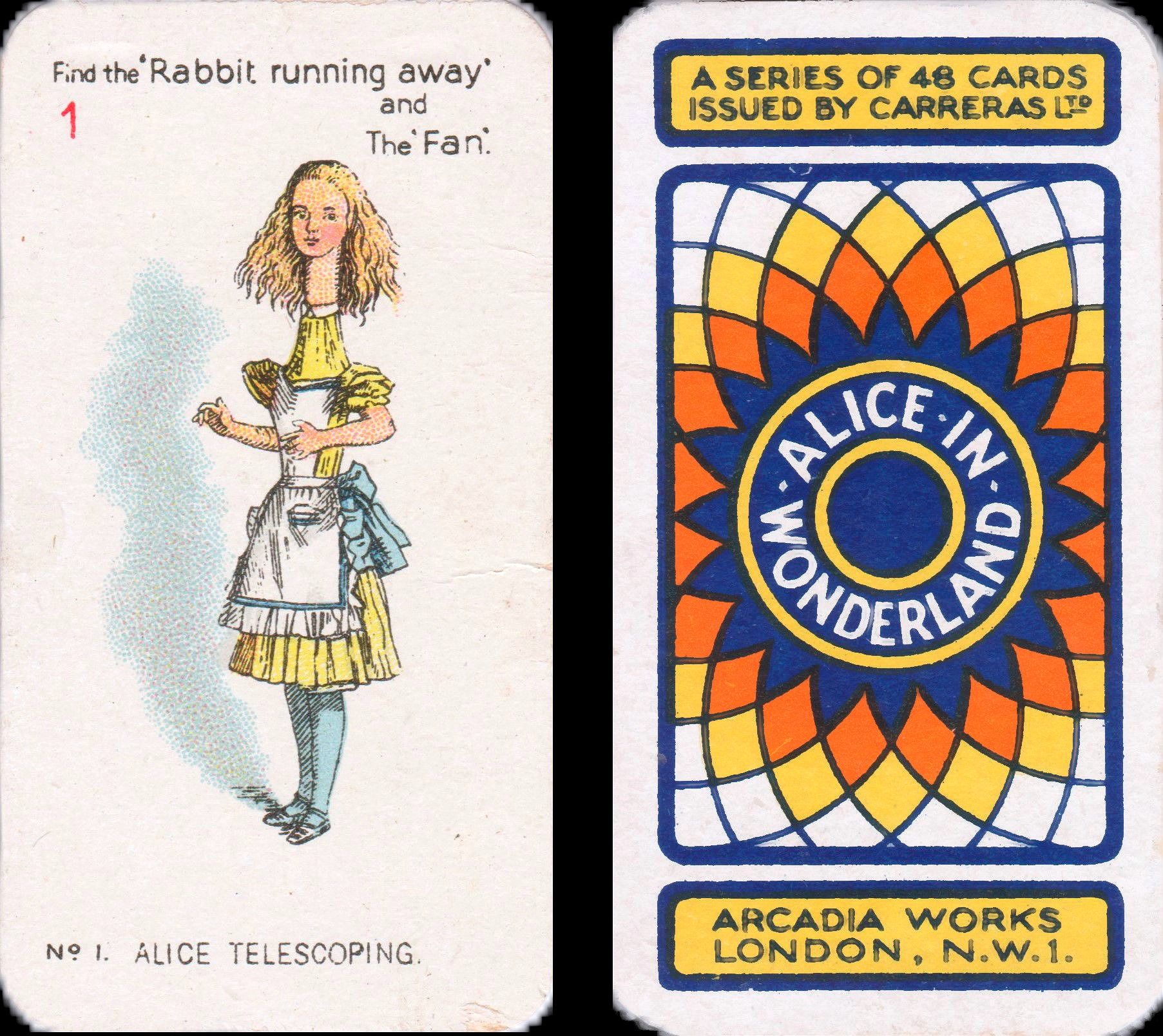

Card n.1 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

A significant example is the Carreras Black Cat cigarette cards from 1930, a series of highly collectible cigarette cards that take up the illustrations of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. While not all of them are exact copies, these images are clearly inspired by Tenniel's original illustrations, likely adapted and colored by E. Gertrude Thomson, as seen in editions such as The Nursery Alice. The cards are often described as "stunning" and "highly collectable", and in collecting circles they are frequently attributed to Tenniel, demonstrating his enduring influence. The artistic representations in these cards show how the aesthetic created by Tenniel for Alice continues to be celebrated and reinterpreted, keeping her contribution to literature and the visual arts alive. Despite their evolution from the originals, the link to Tenniel's work remains evident, underlining how much his illustrations defined Alice's visual imagery.

From 1915 to sound cinema

Alice and the evolution of entertainment

Since the dawn of cinema, Alice in Wonderland has inspired directors and set designers. The 1915 adaptation reflects the pioneering era of silent cinema, when imagination had to fill in technical gaps. The black and white images experimentally translated the language of literature, respecting the aesthetics of the original drawings but inevitably bending to the limits of technology.

However, the transition to sound marked a radical turning point in the language of cinema. And it was in 1933 that Alice in Wonderland found new life on the big screen, thanks to an ambitious production that saw famous protagonists such as Charlotte Henry in the role of Alice and Cary Grant as the Fake Turtle.

And it is in this magical moment of cinema that one of the most touching and extraordinary testimonies also returns: that of the real Alice, Mrs. Alice Hargreaves (born Alice Liddell), the little girl who inspired Lewis Carroll to tell his immortal fantasy.

On Christmas Day 1933, at the age of 82, Mrs. Hargreaves saw the film for the first time at the Southampton cinema, accompanied by her granddaughter. At the end of the screening, excited, she declared:

from Picturegoer Weekly magazine (January 20, 1934)

"Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library"

"I'm very happy to have seen the film," said Mrs. Hargreaves. "It's a delicious production. I am convinced that the Cheshire Cat has really vanished, and that the small oysters flowed in large numbers on the sand.

"The epic battle between Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the fall of Humpty Dumpty, the scene in the kitchen – everything was made tangible to me.

"The film has great significance, because, although the book has been adapted several times for the theater and beautifully illustrated by many artists, it had never been as extraordinary as it is now, populated by people who speak in Carroll's words and resemble Tenniel's drawings.

"The characters are beautifully rendered and the whole thing is a great success. I'm pleased that the costumes and outfits are as faithful as possible to Tenniel's work and that the actors have been careful to stay true to the story written by Carroll.

"I must say that it was not easy to turn fantasy into reality. The actors had to use their own interpretations, but I think they did a great job. I am very satisfied with the film.

"I'm really happy to have seen it. It's a delightful production, and I'm sure it's going to be a great success."

Alice Liddell -Photo by Lewis Carroll - Wikipedia

Mrs. Hargreaves is today the most direct link with Lewis Carroll and everything related to him, since it was to her – then Alice Liddell – that the author told his immortal fantasy during hot summer days along the Thames.

It was only to amuse this real Alice and her two sisters that the story took shape. A close friend of Carroll's convinced him to write it down and publish it, and Alice in Wonderland was given to the world.

On Christmas Day, Mrs. Hargreaves, saw the Alice in Wonderland-inspired film at the local cinema along with her granddaughter Mary Jean Hargreaves. The theatre in Southampton was packed with people eager to find out what impression the film would make on the woman who was the real Alice.

After that magical Christmas screening, Mrs. Hargreaves spent a few more months. He died in 1934, at the age of 82, closing a circle that had begun over seventy years earlier along the Isis river. She had been a muse, a witness to the change of an era, a mother marked by war, and finally a spectator of the cinematic reflection of her past.

Alice Pleasance Liddell Hargreaves in 1932

Wikipedia

She was no longer just a child in a wonderland, but a woman who had gone through the wonders – and shadows – of time.

She was buried at Lyndhurst, in the heart of the New Forest, and her tombstone is simply engraved: "Alice Hargreaves, née Alice Liddell."

A real life that inspired the imagination, and that gracefully guarded Carroll's dream until the end.

WHEN SOUND WASN'T ENOUGH

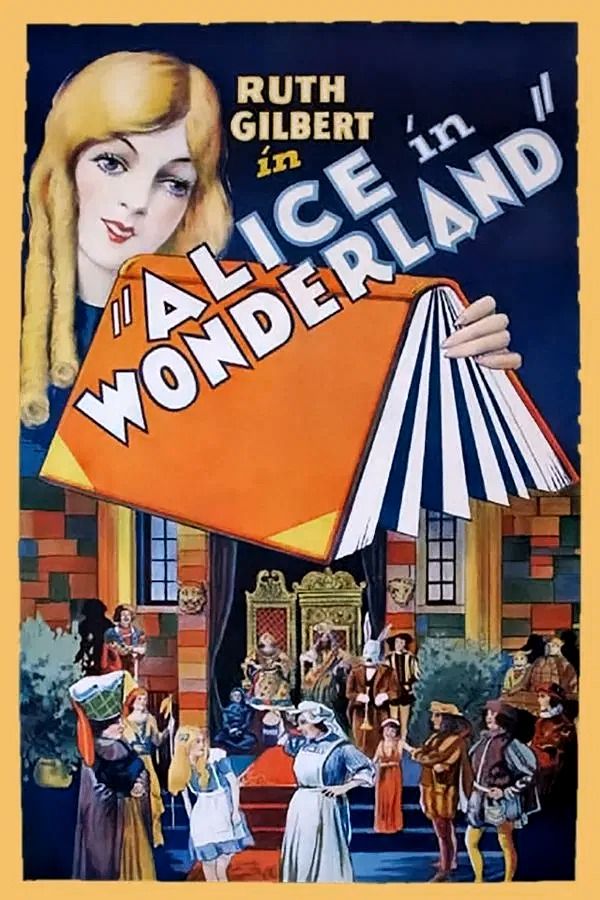

Poster del Film (1931)

Wikipedia

However, between the silence of 1915 and the splendor of the big screen of 1933, there is an almost forgotten but historically significant attempt: the 1931 film, directed by Bud Pollard. It was the first sound transposition of Alice in Wonderland, made with small means and a still uncertain, almost artisanal style. Filmed at the Metropolitan Studios in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and starring Ruth Gilbert as an adult Alice, the film tried to stay true to Carroll's original dialogue, but did so with a poor aesthetic and a theatrical acting that today seems out of time.

Promotional photograph from 1931

Wikipedia

The actors moved in sparse sets, the costumes were rudimentary, and some scenes such as the tea scene or the one with the Queen were more disturbing than surreal. The work went almost unnoticed, and today it remains a fragile but fundamental piece in the mosaic of Carrollian adaptations: an unstable bridge between silent cinema and the dream orchestrated by sound. That failure gave strength to Paramount, which two years later would bring Alice back to the center of the collective imagination with a much more ambitious vision.

Alice in Wonderland (1933)

A Celuloid Enchantment Before Time

Poster del film (1933)

"Courtesy of the site doctormacro.com"

Imagine being in 1933, among the velvets of an elegant cinema while the lights go down. On the screen, a bizarre and enchanted world comes to life, shaped by a technology that is still imperfect but driven by the feverish desire to amaze. It is Alice in Wonderland, Paramount's vision, and the audience of the time is bewitched.

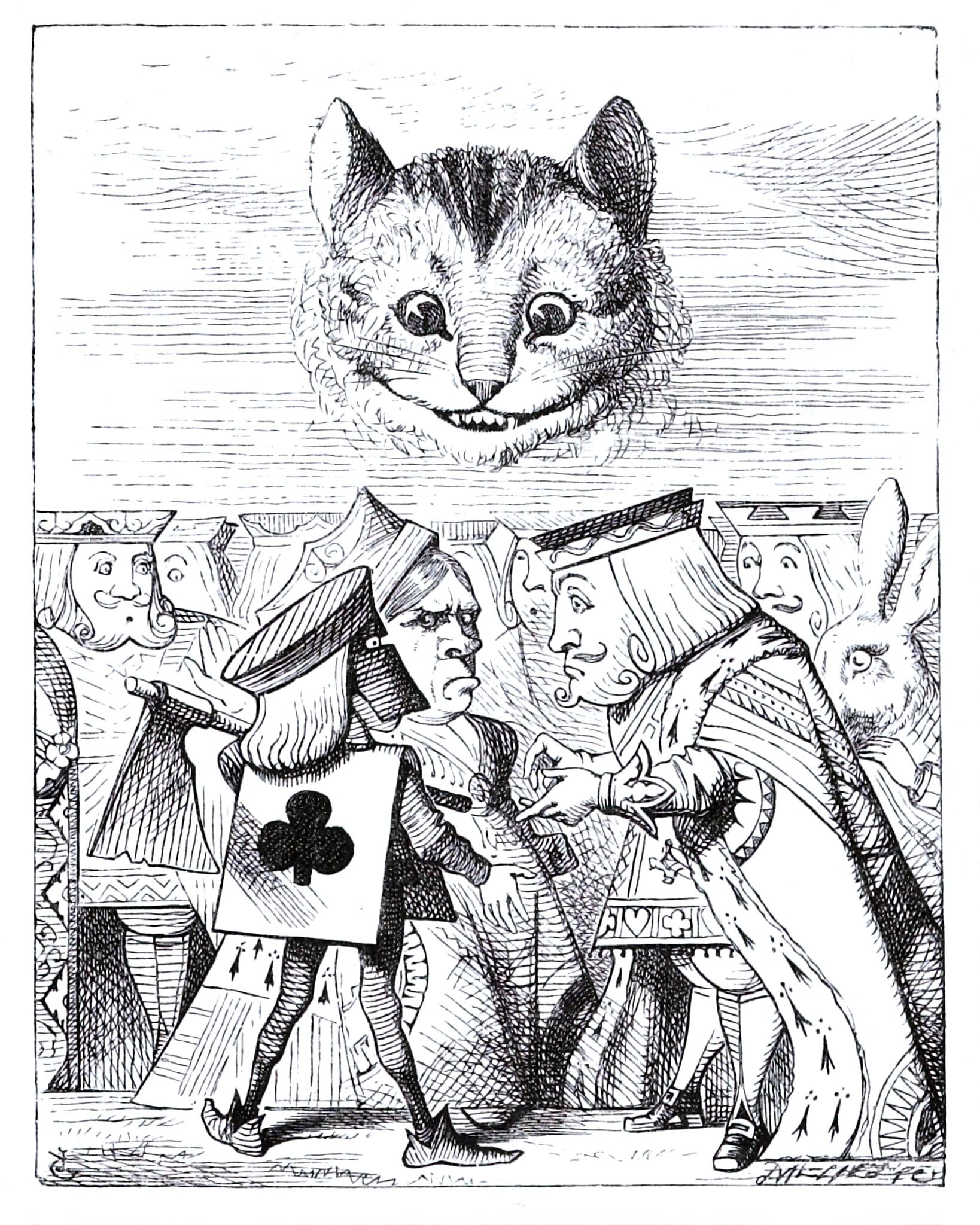

This film was not just an adaptation: it was a daring experiment, a challenge between art and craftsmanship. The costume designers created monumental masks that totally covered the actors' faces, a bold idea for an era when sound cinema was still finding its voice. The result? Figures incredibly similar to Tenniel's illustrations, but animated by famous voices that made each scene a small theater of the absurd.

Charlotte Henry, just seventeen years old, brought to the stage a genuine and melancholic Alice, lost and alive in equal measure. Alongside her, film icons such as W.C. Fields, who enjoys reinventing Humpty Dumpty with sly authority, and a surprising, almost unrecognizable Cary Grant in the role of the False Turtle, demonstrate how imagination can overturn the rules of stardom.

Each sequence seems to be born from a lucid dream: the mad hatter who moves cups as if they were dancing alone; the Cheshire Cat that fades intermittently; oysters chasing each other like children on the beach. And then the dialogues: even with the muffled voice of the speakers of the time, Carroll's words remain intact in their enchanting absurdity.

This Alice was not just cinema: it was a magic mirror. A carnivalesque refraction of the Victorian imagination in a Hollywood that was discovering the hypnotic power of the sound screen. A parenthesis of wonder in the midst of a Great Depression, in which even adults allowed themselves to become children again, at least for an hour and a half.

Tenniel comes to life

Actors, costumes and cigarette cards in the visual imagination of the Thirties

If the 1933 film is a portal that invites us to cross the mirror, it is only by observing it closely, behind the scenes, among hand-sewn fabrics and gazes hidden behind theatrical masks, that we understand the true ambition of that project: not simply to adapt Lewis Carroll, but to embody Tenniel.

Because every frame, every costume, every pose of the actors seems to chase not reality, but that particular Victorian style that Sir John Tenniel had traced almost seventy years earlier. His characters, born from ink and engravings, find a second life here: restless, poetic, often surreal.

And this is precisely the heart of this chapter: to explore who gave body to those figures, how the costumes that replicate the illustration were made, and why those small collectible cards, the cigarette cards, give us back today the same enchantment as then, in pocket scale.

THE COSTUMES

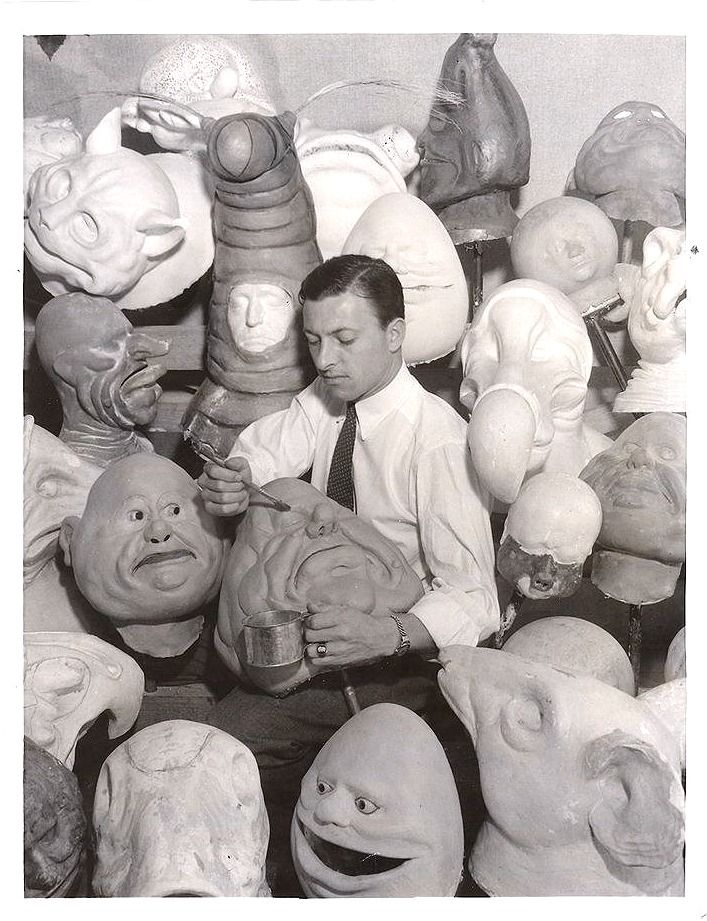

Wally Westmore

Pinterest.com

Behind the bizarre masks, pointed faces and disturbing smiles of Alice in Wonderland (1933) lies one of the most influential hands of period cinema: Wally Westmore, chief make-up artist of Paramount Pictures and member of a legendary Hollywood make-up dynasty. In his silent laboratory, with glue, latex and powder, Westmore built not only the faces of the characters, but the visual key to the entire film.

For this adaptation crowded with famous actors and nonsense creatures, Westmore achieved an unprecedented feat: making up the entire cast with semi-rigid masks that leaked expressions and mimicry. The technology of the 30s did not offer digital effects: everything had to be done by hand, with precision craftsmanship and theatrical sense. The result? Unrecognizable actors but still alive under layers of foam rubber and cosmetic plaster.

Cary Grant

Pinterest.com

Faces such as those of Cary Grant (False Turtle), W.C. Fields (Humpty Dumpty) or Gary Cooper (White Knight) were reshaped to fit surreal, caricatured, half-fairytale, half-nightmare characters. Yet, thanks to Westmore's work, emotions still leaked through, as if masks were breathing. Even less central figures from the Fish to the Frog, from the Mouse to the Griffin possessed minute details: false eyelashes, sculpted teeth, colored plumage, flickering mustaches.

Makeup, in this film, is not just an aesthetic effect: it is narrative language, identity, visual satire. Each character moves as if in a badly sewn dream, but it is precisely this difference in height between actor and mask that returns the unsettling effect of Wonderland. It is nonsense made epidermis.

Westmore's signature is present in every scene, even if the viewer does not notice it: in the disturbing symmetry of the characters, in the grotesque plasticity of the eyes, in the hand-drawn mouths, often off-axis, as if the features themselves were trying to escape from the face. His work anticipates by decades the use of makeup as an expressive tool in fantasy and the surreal.

Today his contribution is often forgotten, but without him Alice in Wonderland would have been a film populated by familiar faces with a few ears glued to them. Instead, thanks to Westmore, it has become a masked ball of the absurd, where each face tells a story... even if no one can really explain it.

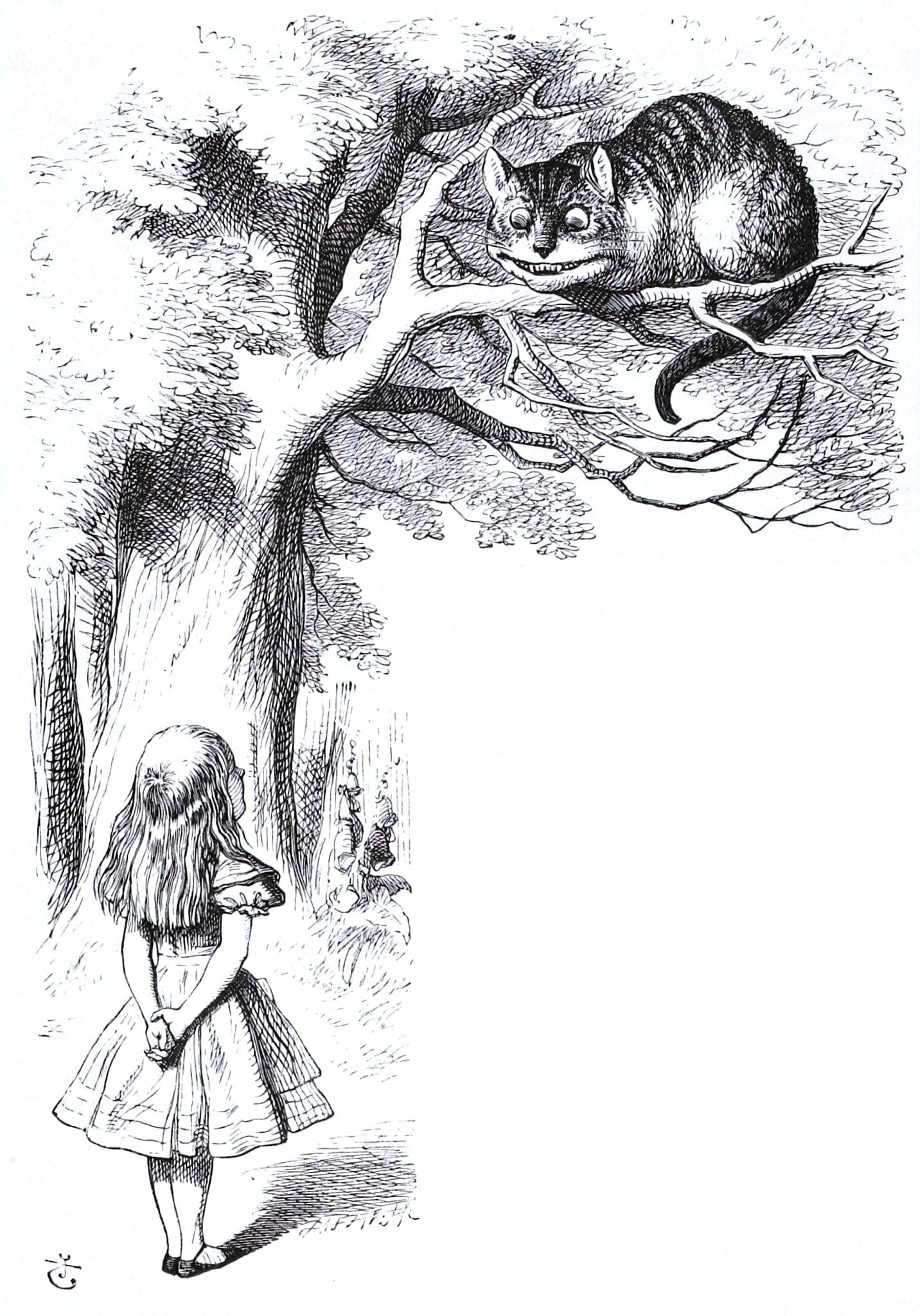

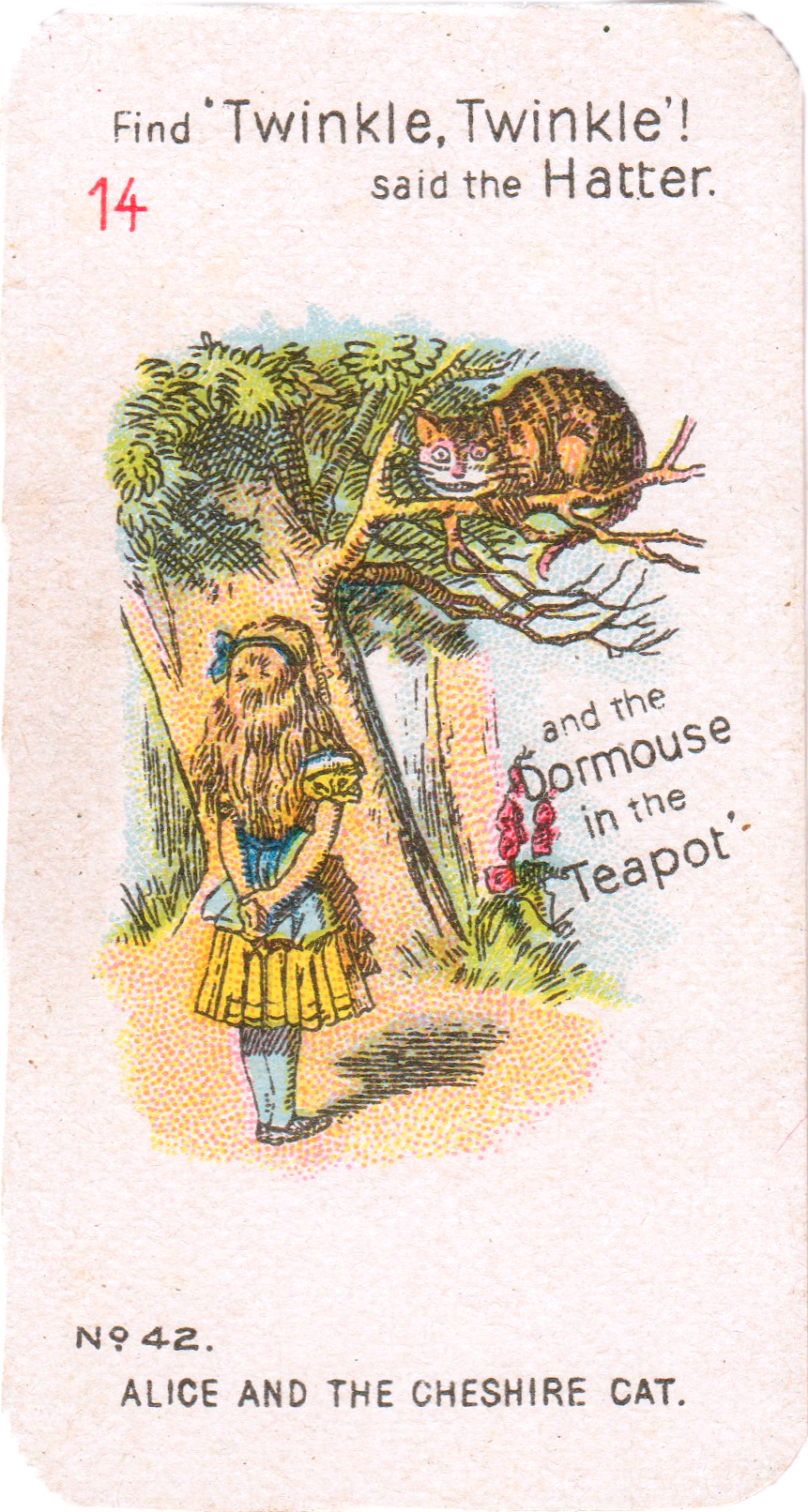

ALICE

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Wikipedia

Card n.25 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Charlotte Henry (1933)

Pinterest.com

In the heart of this upside-down world, among furious queens, talking animals and overturned logic, there is her: Alice, the little girl who observes, questions, gets lost and finds herself. In the film of the thirties, it is Charlotte Henry, just nineteen years old, who embodies her in her first leading role. Yet, his Alice is not just a narrative figure: it is the emotional axis around which the entire Wonderland revolves.

Henry brings to the screen an Alice who is never a caricature: she is curious but composed, dreamy but lucid, always poised between childhood and awareness. Her wide-open eyes are not only those of an astonished child, but those of a young woman who begins to question the meaning of things. In a world where everyone speaks in riddles, Alice is the only one who searches for meaning.

The costume, simple and faithful to Tenniel's illustrations, blue dress, white apron, headband, makes her immediately recognizable. But it is her presence that makes her alive: Charlotte Henry moves with theatrical grace, reacts with genuine amazement, and manages to maintain her humanity even when everything around her is mask and parody.

Alice among grotesque creatures, Alice who listens, who runs, who stops to think. It is the golden thread that holds the dream together, the emotional compass of the viewer.

And perhaps this is precisely the secret of the film: in the midst of a carnival of absurdity, it reminds us that growing up, like Alice, means learning to walk in the wonderful without getting lost.

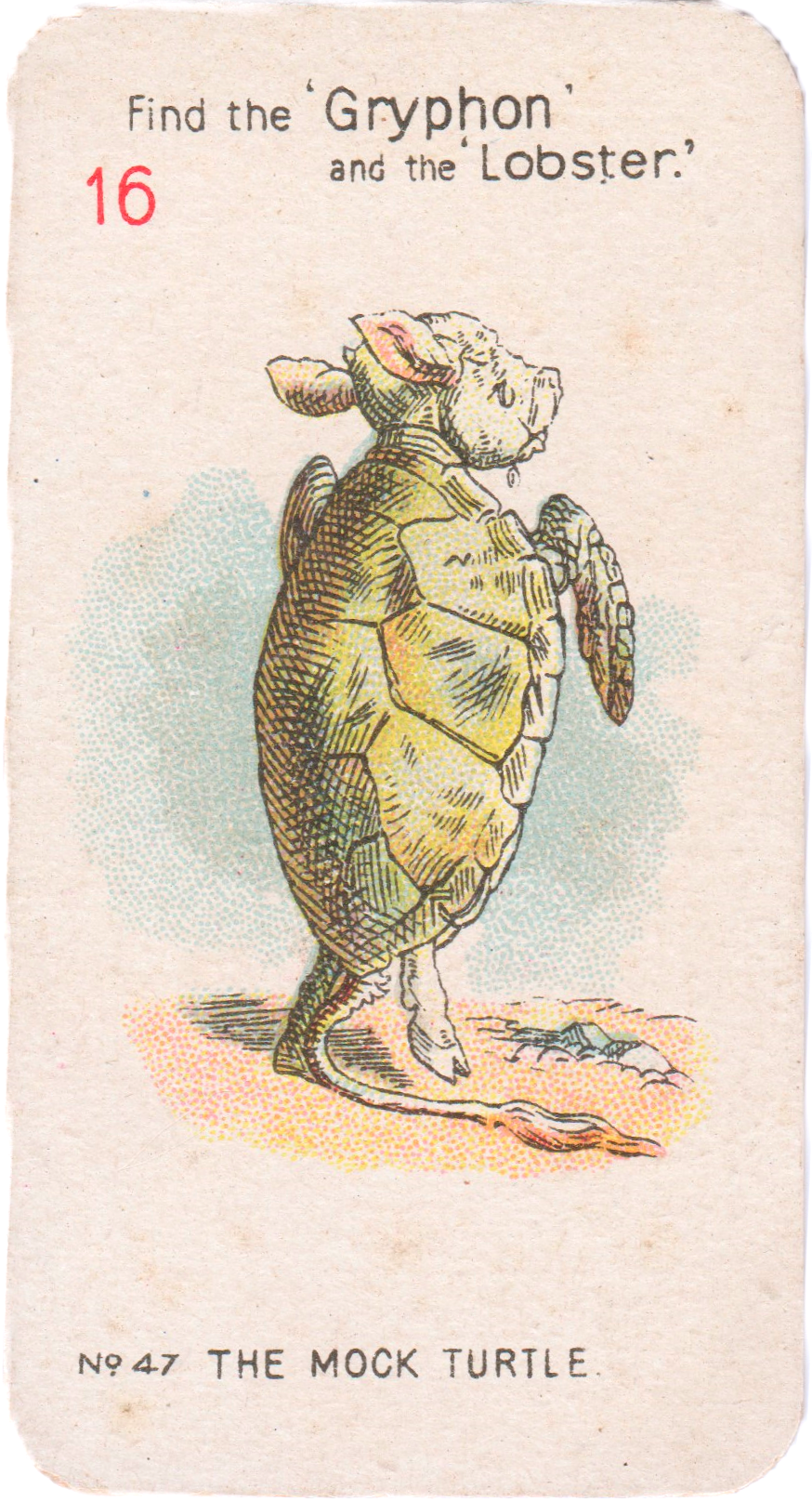

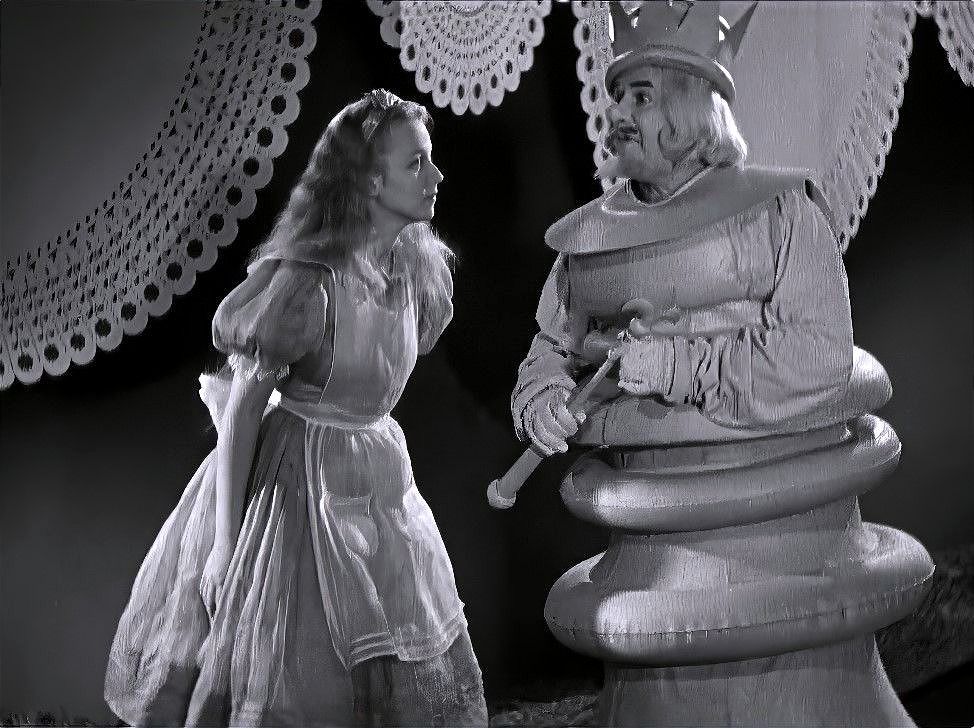

THE MOCK TURTLE

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Wikipedia

Card n.47 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

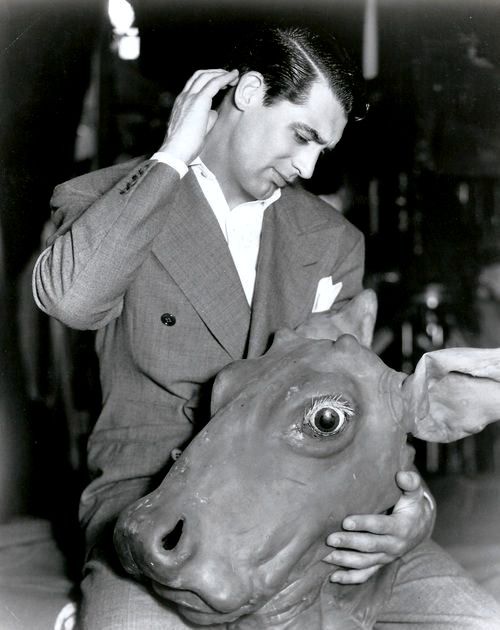

Cary Grant and the costume worn in the film (1933)

"Courtesy of the site doctormacro.com"

Among the most enigmatic creatures in Wonderland, the Mock Turtle is perhaps the most poignant. A hybrid being, half turtle and half calf, born from a Victorian pun (the "mock turtle soup" was a cheap soup that imitated that of a real turtle), yet in the 1933 film he becomes something more: a sorrowful, poetic, almost Shakespearean figure.

Under the heavy costume, Cary Grant, already a rising star in Hollywood, gives a surprising performance. His voice, also recognizable through the mask, gives the character a melancholic sweetness, a sense of nostalgia for a past that perhaps never existed. Its movements are slow, almost aquatic, as if it really carried the weight of an invisible shell.

The scene in which he tells Alice about his "school" childhood under the sea, with the teacher Tortoise "because he taught us", is a small masterpiece of nonsense and tenderness. Grant manages to make the absurd believable, transforming a grotesque character into a fragile and memorable creature.

The images with the bovine-headed costume, the fins and the Victorian collar perfectly convey this ambiguity: a comic mask that hides a sad soul. And in this, perhaps, the False Turtle is the character that most embodies Carroll's spirit: a smile that bends into melancholy, a game that becomes reflection.

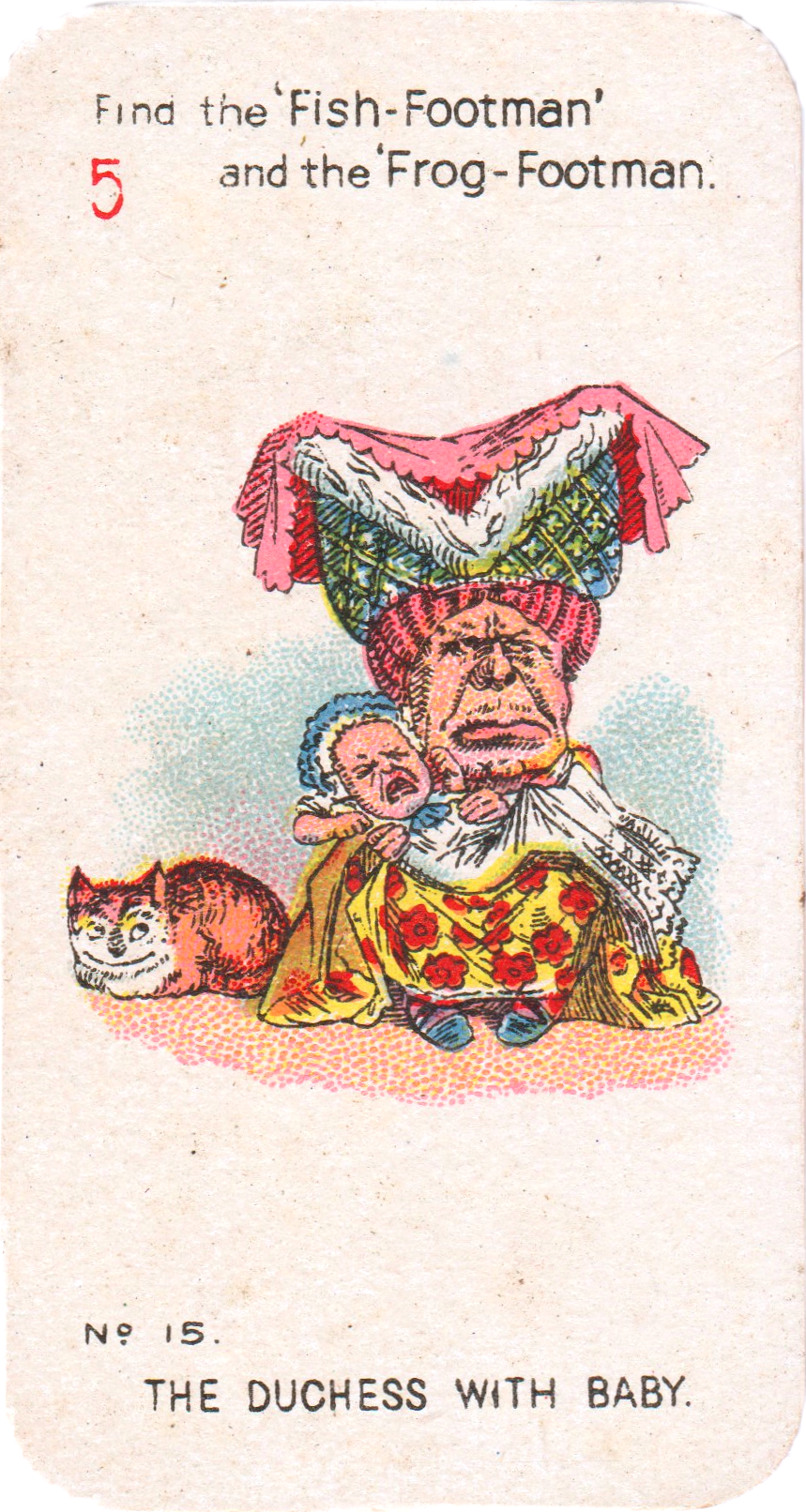

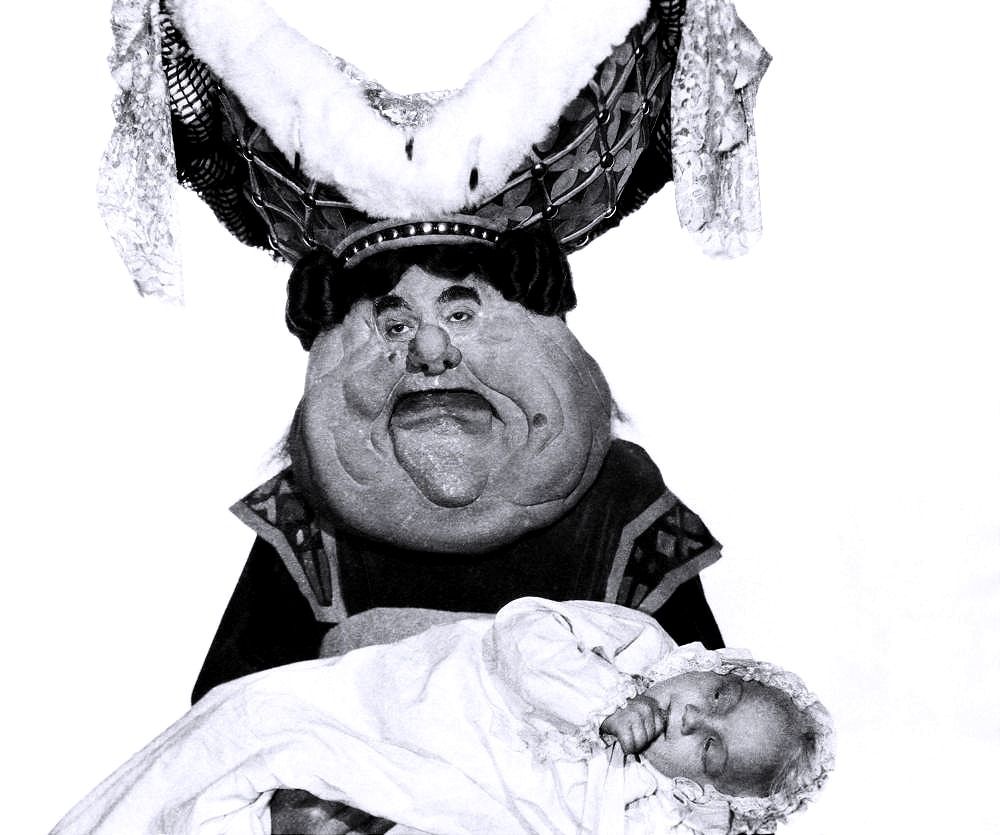

THE DUCHESS

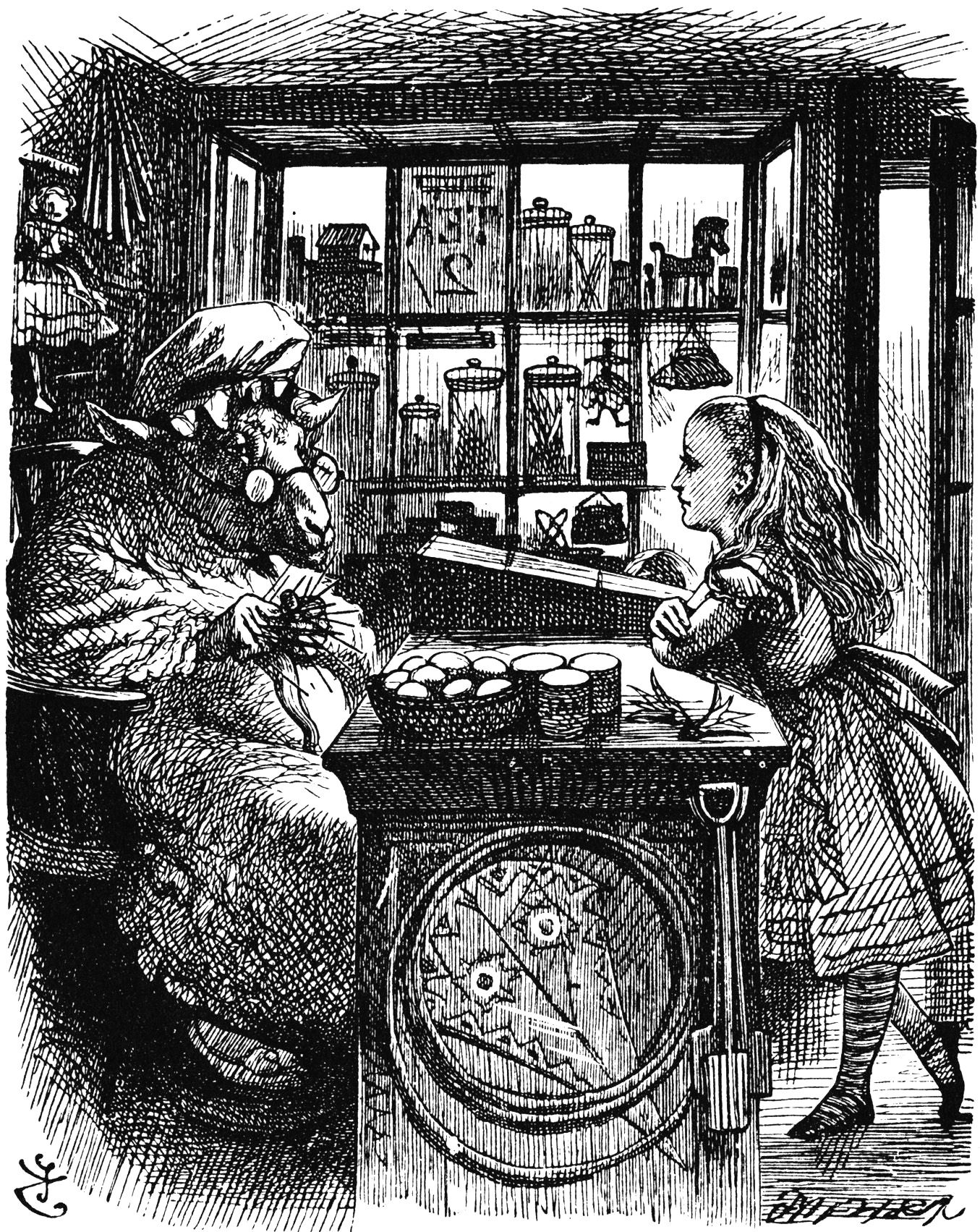

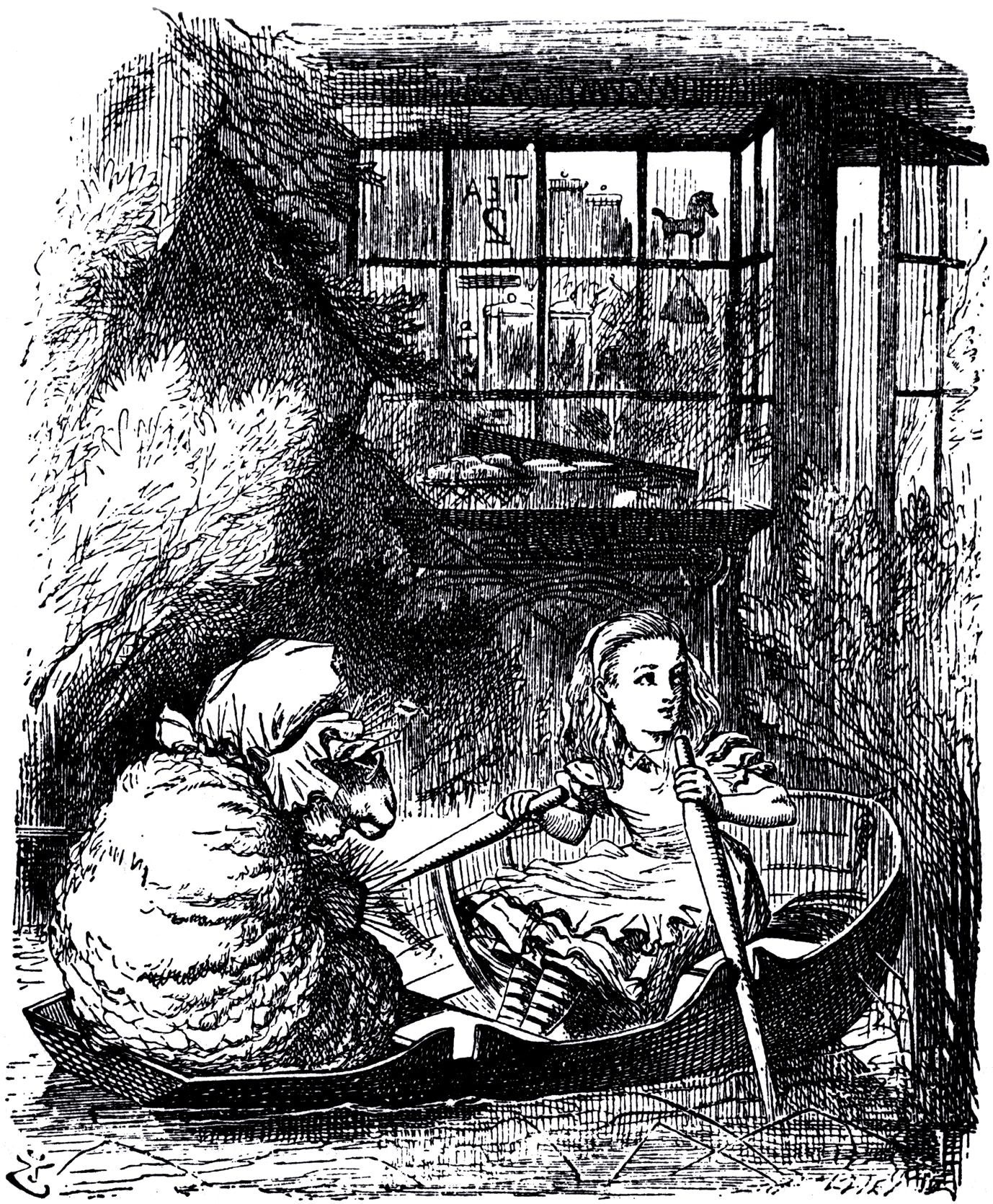

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Wikipedia

Card n.21 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Charlotte Henry and Alison Skipworth, in the center the Duchess's mask (1933)

Pinterest.com

In Carroll's world, the Duchess is an ambiguous figure: unpleasant but charming, gruff but suddenly affectionate. In the film of the thirties, Alison Skipworth makes a memorable portrait of him, accentuating the grotesque side of the character with an imposing stage presence and a hoarse voice, almost like a Victorian matron.

The costume is among the most theatrical in the film: a disproportionate head, hooked nose, ruddy cheeks and a baroque dress, which makes her look like she came out of an eighteenth-century satirical painting. Yet, under that caricatured mask, Skipworth manages to instill in the Duchess a strange humanity: he laughs coarsely, gets too close, speaks too loudly, but there is something tender in his clumsiness.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.15 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Alison Skipworth, the Duchess, Billy Barty, the child (1933)

Pinterest.com

The scene in which he holds the newborn in his arms (who then turns into a piglet!) is a small masterpiece of surreal comedy. His interaction with Alice is made up of contrasts: authoritarian and intrusive, but also strangely affectionate, like a weird aunt you never know whether to hug or avoid.

These images show this ambivalence very well: a figure that makes you laugh and unsettle at the same time, perfectly in line with Tenniel's spirit. And Skipworth, with his theatrical experience, knows how to dominate the scene even under kilos of makeup and fabric.

THE GRIFFIN

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.48 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

William Austin, Charlotte Henry e Cary Grant (1933)

Pinterest.com

In Carroll's fantastic bestiary, the Griffin is a mythological creature with a lion body and eagle wings, but in the 1930s film he becomes something more: a living caricature of authority that never takes itself too seriously. He was played by William Austin, a British actor with a long career, known for his eccentric roles and his expressive mimicry, perfect for a character as grotesque as it is theatrical.

The costume is among the most spectacular in the film: a feathered head with a curved beak, wide eyes and a lion's mane, all mounted on a massive and feathered body that seems to have come out of a medieval engraving. But it is the way Austin moves jerkily, with wide gestures and indignant looks that gives the Griffin a personality all its own: a mixture of barracks sergeant and vaudeville actor.

In the story, the Griffin accompanies Alice to the False Turtle and presses her with guttural verses such as "Hjckrrh!", which in the film become a kind of comic tic, a theatrical grunt that breaks the rhythm and makes you smile. He is impatient, sarcastic, yet strangely protective of Alice, like a grumpy old uncle who becomes attached in spite of himself.

William Austin manages to render all this even under kilos of feathers and latex: his hoarse voice, cockney accent and rigid posture transform the Griffin into a memorable figure, who seems to have come out of a disturbed dream... or a comedy of the absurd.

The images show this ambiguity very well: a creature that makes you laugh, but that also commands a certain respect, as if it knew something that we don't know. And perhaps it is just like that: the Griffin is the guardian of a nonsense that needs no explanation.

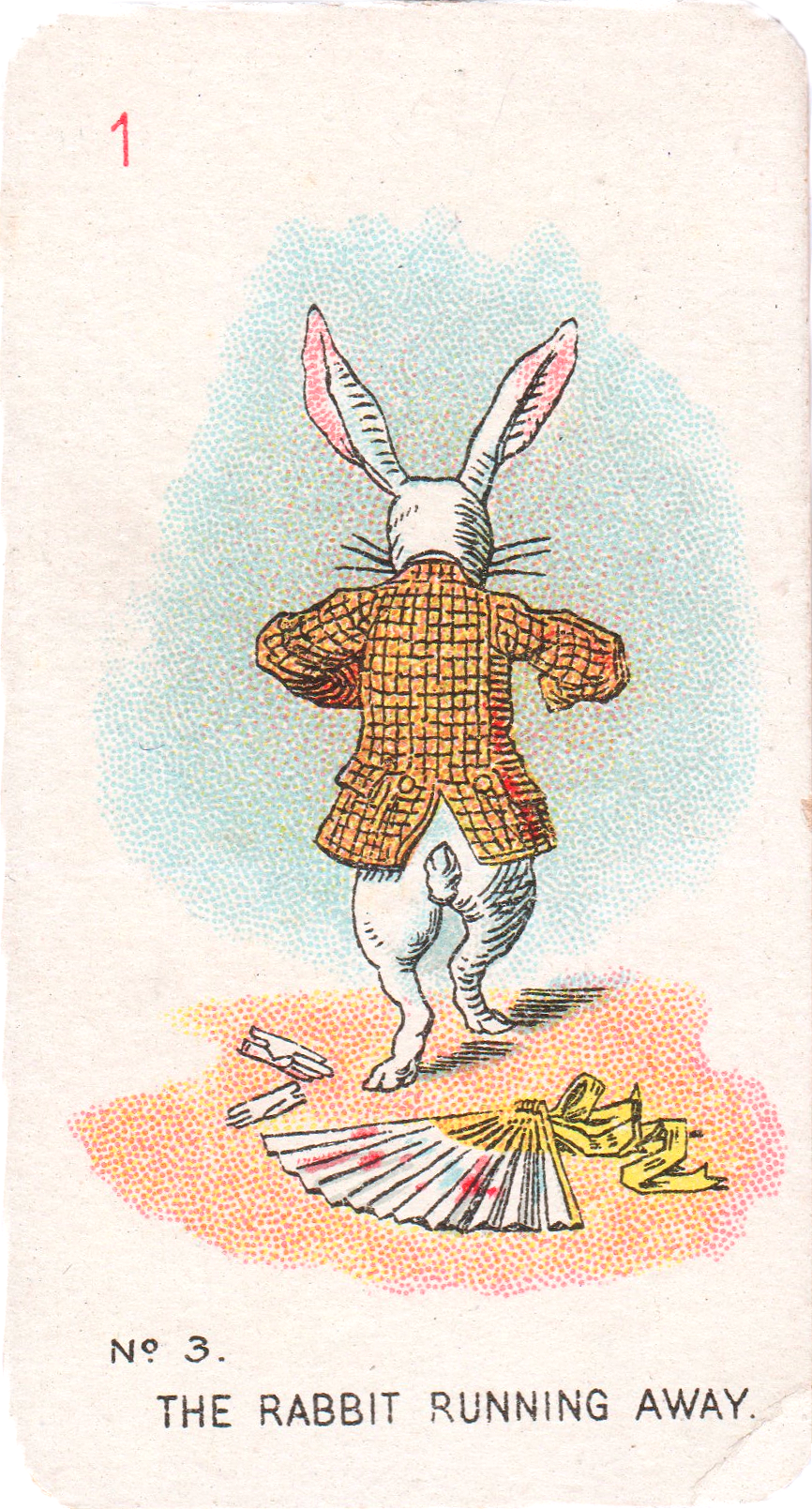

THE WHITE RABBIT

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.28 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)(personal collection)

Poster "ALICE IN THE WONDERLAND"

"Courtesy of the site doctormacro.com"

In the 1930s film, the iconic figure of the White Rabbit takes shape thanks to Richard "Skeets" Gallagher, an American actor known for his roles in the brilliant films of the 1920s and 1930s. With his fast talk and restless gaze, Gallagher proves to be a perfect choice to embody the terror of delay that defines this character: he is not just a talking rabbit, but a walking anxiety in a waistcoat. The costume is among the most memorable in the film: a giant sculpted rabbit head, wide-open and panicked eyes, a mustache as rigid as pins, and an elegant period gentleman's suit, complete with a pocket watch. It is Tenniel who comes to life, but filtered through the eccentric gaze of Hollywood cinema. Gallagher doesn't just wear a costume: he inhabits it completely. His nervous movements, the continuous jerk of his neck, his hands shaking while he consults his watch, all tell of a creature who has made delay an existential condition.

Card n.3 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

His "I'm late! I'm late!" (rendered in Italian with the famous "It's late! It's late!") it is more than a joke: it is a mantra, a lament, an anxious soundtrack that accompanies Alice in her entry into paradox. Yet, despite the caricature, Gallagher manages to maintain a touch of vulnerability. Under the alarmed gaze of the Rabbit, you can sense the real fear of the consequences, especially when the Queen of Hearts enters the scene. He is a funny character, yes, but also a mirror of our daily fears: that of not being up to it, of arriving too late, of not having any more time. And in the visual heart of the film, between masks and feathers, he remains the accelerated beat that sets in motion all the wonderful chaos.

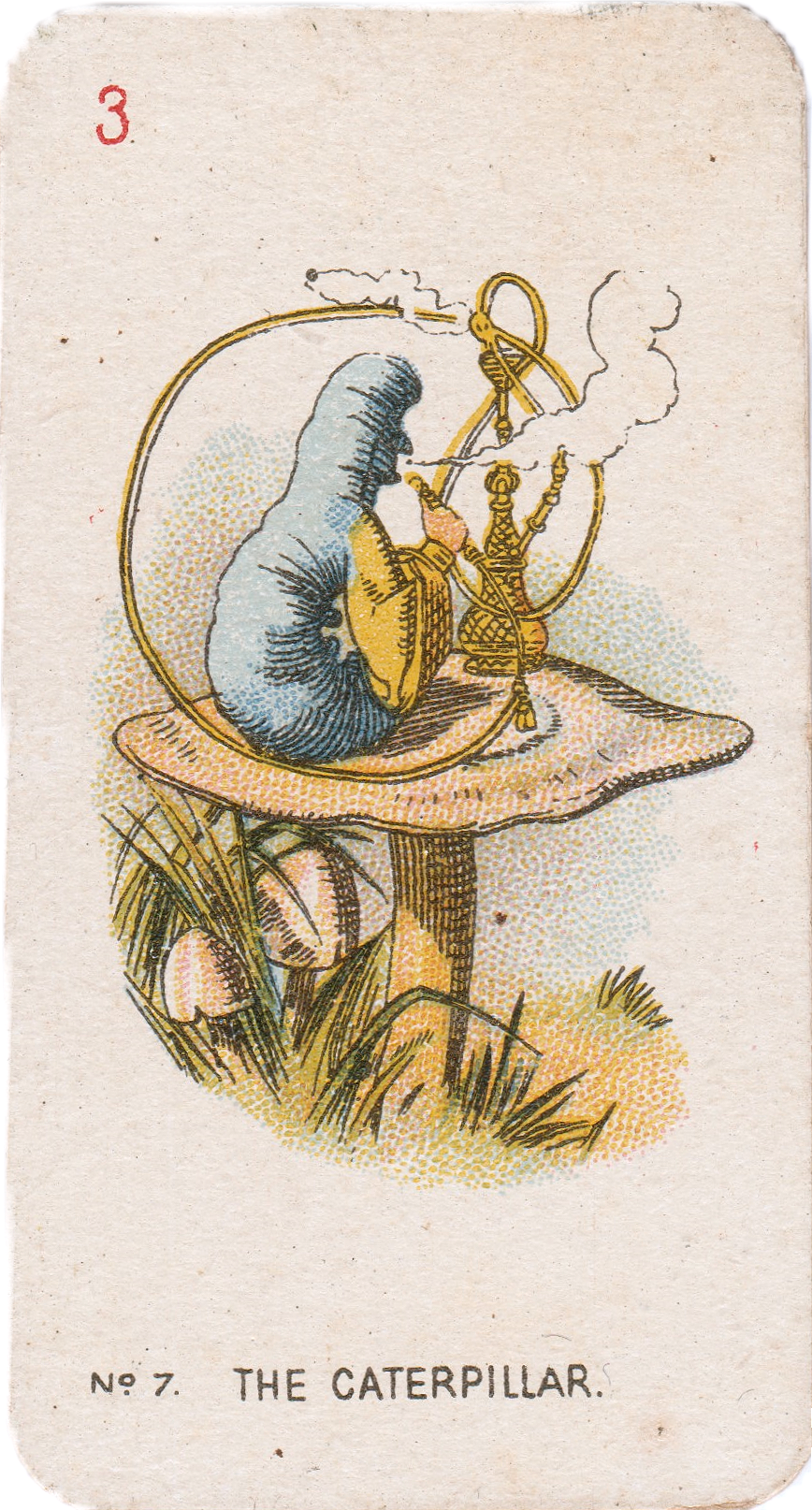

THE CATERPILLAR

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Wikipedia

Card n.3 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Ned Sparks and Charlotte Henry

Pinterest.com

Among the most enigmatic and fascinating characters in Wonderland, the Caterpillar is perhaps the one who most embodies the mystery of identity. Sitting on a mushroom, enveloped in spirals of smoke and an air of languid superiority, he asks Alice the most destabilizing question of all: "Who are you?"

In the 1933 film, he is played by Ned Sparks, a Canadian actor famous for his impassive face and nasal and monotonous voice, a perfect choice to give the Caterpillar an ironic, detached, almost provocative tone. Sparks doesn't just act: he turns every word into an enigma, every pause into a silent judgment.

Ned Sparks

Pinterest.com

The costume is among the most surreal in the film: a segmented body, with flickering antennae and a long pipe from which swirls of artificial smoke come out. Sparks' face is only partially visible, set in a mask that makes him look more like a statue than a living creature. Yet, it is precisely this immobility that makes him hypnotic: it is the character who does not move, but makes everything move inside Alice.

The scene is built as a small theater of the absurd: the Caterpillar speaks in aphorisms, is elegantly offended, and finally literally transforms leaving behind only cryptic advice and an echo of smoke. It is a suspended, almost dreamlike moment, which in the film takes on a rarefied visual quality, as if time had stopped.

The images show this atmosphere well: the scenic mushroom, the pipe, the segmented costume and the fixed gaze. It is Tenniel who meets symbolist theater, with a touch of surreal cabaret.

And perhaps this is precisely the secret of the Caterpillar: it does not give answers, but forces you to ask questions. And in a world where everything changes shape, he is the only one who already knows what he will become.

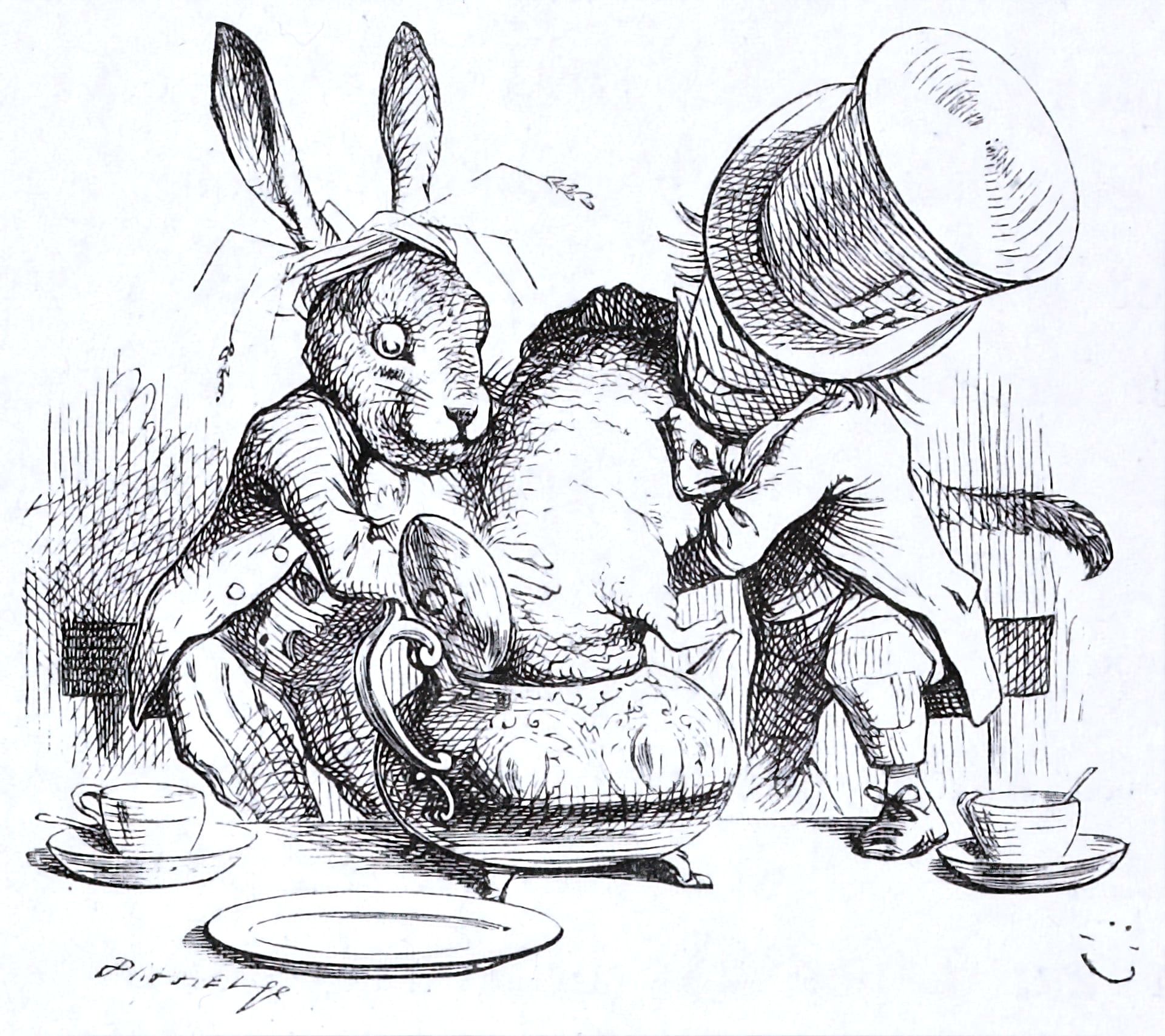

THE MAD HATTER

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Wikipedia

Card n.40 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Edward Everett Horton

"Courtesy of the site doctormacro.com"

In the 1933 film, the Mad Hatter comes to life thanks to the unforgettable performance of Edward Everett Horton, an actor with sophisticated comedy and nervous irony, perfect for embodying a man who knows no time, or perhaps knows it all too well. Horton, famous for his surreal gentleman roles in American comedy, plays the role of the Hatter as if he had sewn them on himself with a needle of nonsense and theater thread.

The costume, faithfully inspired by John Tenniel's illustrations, is among the most recognizable of the entire film: a disproportionate top hat with the now legendary "10/6" label tucked into the brim (which indicated the price: ten shillings and six pence), a large and crumpled jacket, an out-of-scale bow tie and eyes painted so as to always be wide, perpetually on alert. Yet, under this grotesque aesthetic, Horton manages to create a very human character: dazed, verbose, but also fragile, like those who act in order not to collapse.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.41 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Pinterest.com

Mad Hatter Edward Everett Horton with the March Hare Charles Ruggles & Charlotte Henry

Pinterest.com

The tea scene with the March Hare and the Dormouse is a real exercise in choreographic nonsense: saucers flying, unanswered questions, laughter out of time. And above all that suspended moment in which time rebels and stops flowing. Horton dominates the scene like a conductor of chaos, voicing a character who is not only comical, but almost disturbing, as if he knows something that the rest of the world has forgotten.

But even before cinema, before papier-mâché masks and absurd jokes, the Mad Hatter may have been real. And he bore a singular name: Theophilus Carter.

Theophilus Carter (1894)

Pinterest.com

An Oxford cabinetmaker, known in the city for his eccentricity and for his shop overflowing with improbable inventions, Carter spent his days standing in the doorway, always with a top hat well fitted on the nape of his neck. He had the air of a character from a humorous novel: tall, lanky, with marked features and a taste for the bizarre. He was known by all students, professors, children as "the Mad Hatter of Oxford".

We don't know for sure if Lewis Carroll (who lived and taught a few steps away) observed it carefully. But it is said that John Tenniel, called to illustrate the book, took inspiration from Carter to draw the figure of the Hatter: pointed chin, aquiline nose, very high cylinder. A resemblance defined as "unmistakable" by more than one contemporary.

Carter's inventions strengthen the link with Alice's universe: her "plumbing wake-up bed", for example, was intended to literally catapult the sleeper out of the mattress at the appointed time. A gimmick perfectly worthy of a tea between the March hare and the Dormouse, rather than a Victorian technical catalog.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.35 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

The Mad Hatter is not just a grotesque character or a parlor buffoon of the absurd: he is the distorted reflection of a world that has lost control of its time, and perhaps even of its meaning. Whether he is played by Edward Everett Horton with feverish gestures and a voice out of tune with logic, or glimpsed in the eccentric features of Theophilus Carter on the threshold of Oxford, the Hatter remains a liquid symbol: he mutes with mirrors, but continues to look us straight in the eye.

With his top hat too high and his tongue too loose, he invites us to sit at a table where no one has the role they should have, and where the rules exist only to be reformulated with every sip of tea. In an era that runs fast, he is the voice that reminds us that perhaps it is precisely in stopping and lingering, in asking unanswered questions that we can rediscover a sense of wonder.

In his eternal five o'clock tea, the Hatter does not ask us to understand. He asks us to listen. And, perhaps, to smile.

THE CHESHIRE CAT

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.27 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Richard Arlen & Charlotte Henry

Pinterest.com

In the kaleidoscopic 1933 film adaptation, the Cheshire Cat is one of the most mysterious and fascinating appearances. Unlike other characters, he does not have a body that moves on stage, nor a theatrical costume to wear: he is a floating presence, a face that appears among the branches and vanishes leaving behind only a smile just like in Tenniel's illustrations.

To lend him his voice was Richard Arlen, an actor known for his leading roles in silent cinema and in the early years of sound. But in the case of the Cat, Arlen does not appear physically: his interpretation is purely vocal, and for this reason even more evocative. His tone is calm, ironic, almost hypnotic, perfect for a character who does not give answers, but sows doubts.

The visual representation of the Cat was a small technical marvel for the time: an animated feline head, probably a puppet or a mechanical mask, made "ghostly" thanks to an optical superimposition. The eyes sparkle, the mustache barely moves, and the smile, that famous smile, remains suspended even after the face has vanished. It is a simple but very powerful effect, which anticipates by decades the symbolic use of invisibility in fantastic cinema.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.42 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

In the context of the film, the Cat appears briefly but leaves an indelible imprint. He is the one who introduces Alice and the viewer to the concept of madness as a rule, not as an exception. His sentences are ambiguous, his advice seems more like riddles than helps. Yet, in that upside-down world, he is perhaps the only character who knows exactly what is happening.

The choice to entrust the role to Richard Arlen was curious and, in a certain sense, brilliant: an actor known for his physical presence, reduced to a voice and a smile, becomes the very essence of the Puss, an idea more than a body, a concept more than a character.

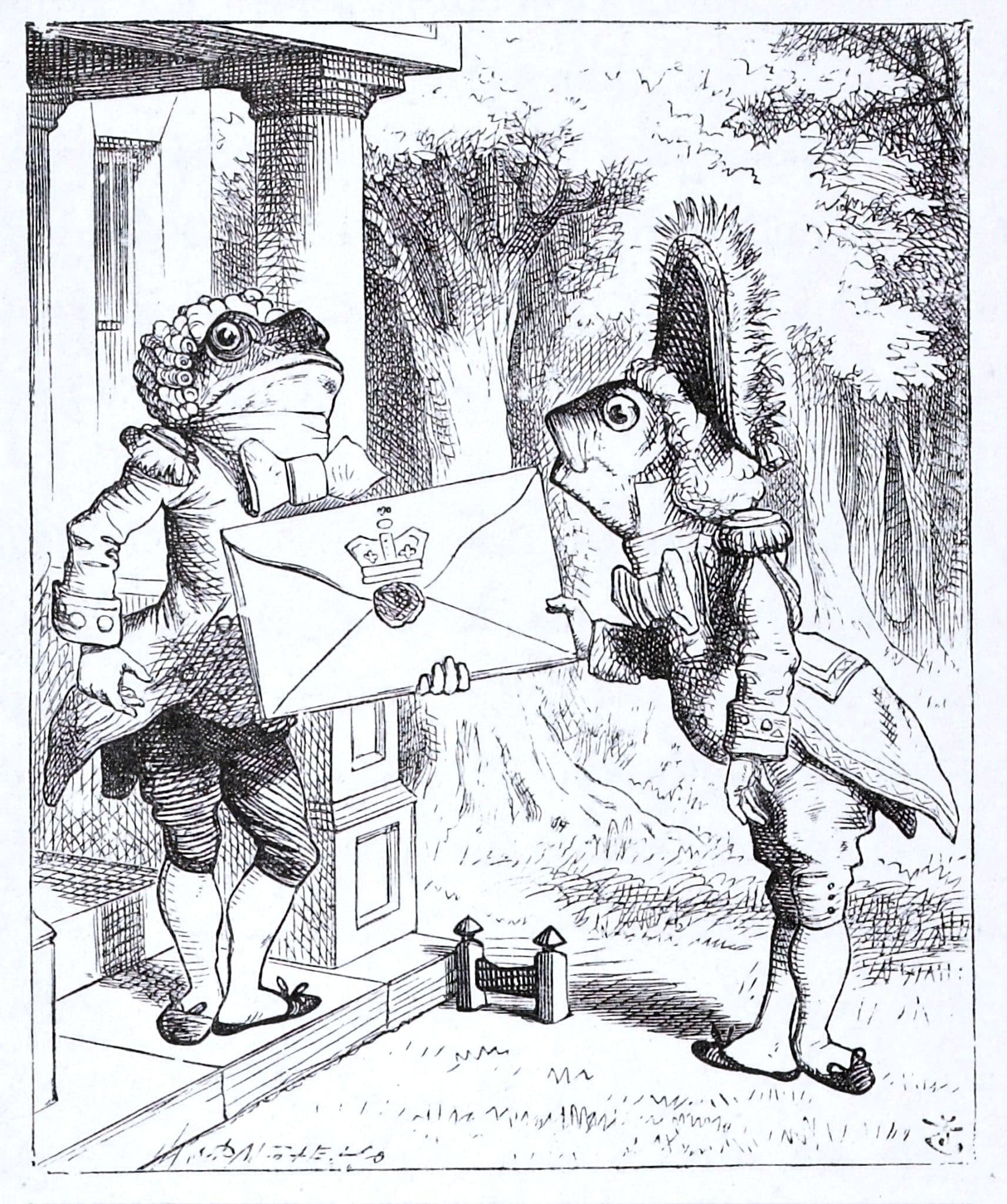

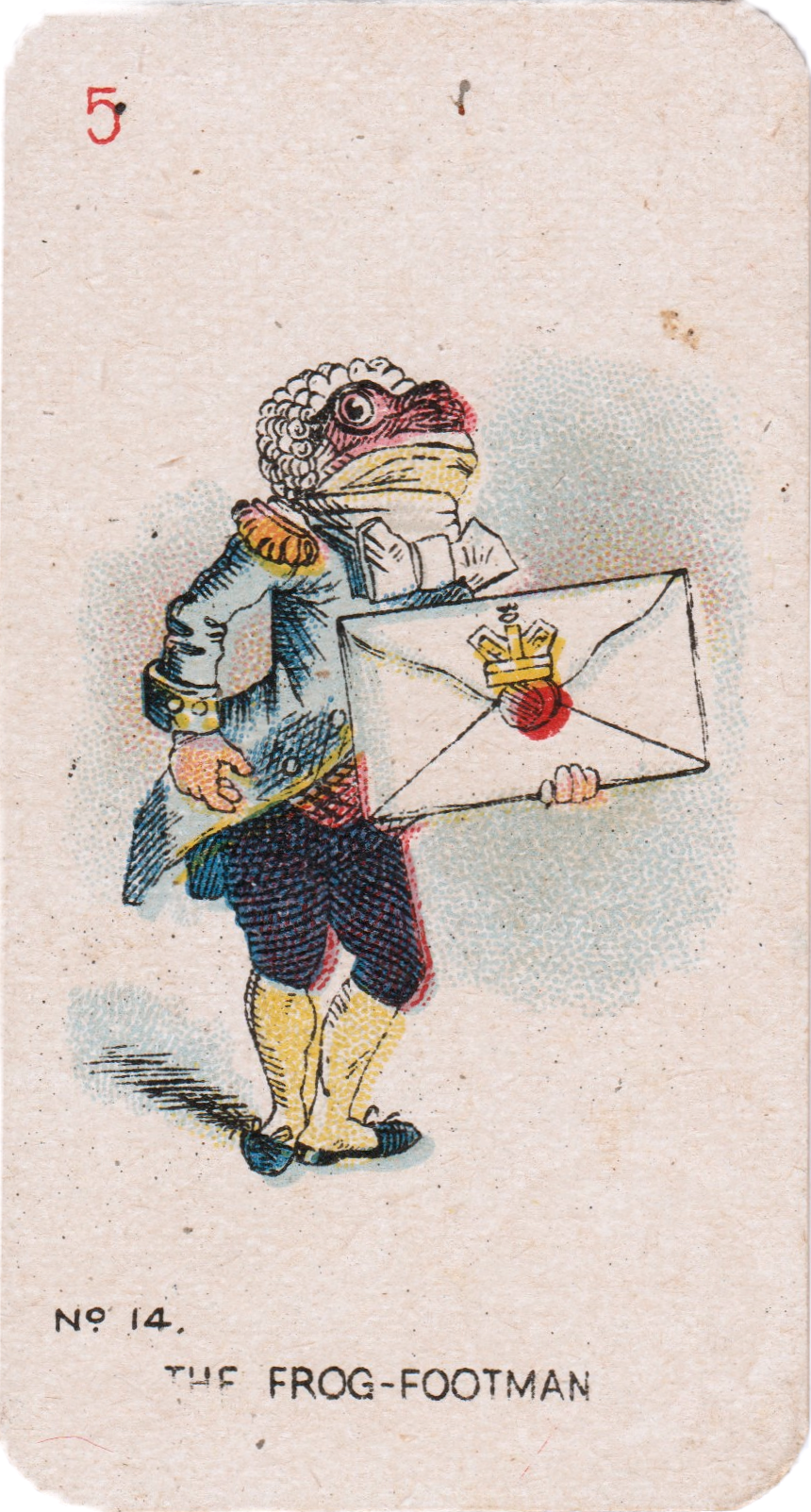

THE FROG AND THE FISH

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.14 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Sterling Holloway

Pinterest.com

Card n.13 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Roscoe Ates

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film, among the most eccentric folds of Wonderland, two characters peep out who seem to have come out of a Victorian farce: the Frog and the Fish, ceremonial servants of the Duchess, protagonists of a scene as brief as it is memorable. To play them were Sterling Holloway (the Frog) and Roscoe Ates (the Fish), two character actors with a strong comic vein, perfect for embodying the bureaucratic absurdity that Carroll loved to ridicule so much.

The scene is taken from the chapter in which Alice approaches the Duchess's house and witnesses an exchange of messages between the two: the Fish, in lackey livery, delivers an official invitation to the servant Rana, who receives it with exasperating slowness, between bows, stammers and ceremonial gestures. In the film, this dynamic is accentuated by grotesque costumes: the Frog has bulging eyes, wrinkled skin and a butler's suit that is too loose; the Fish, on the other hand, is wrapped in a shiny livery, with rigid fins and a perpetually disoriented expression.

The contrast between the two is comical and surreal: one stutters, the other nods without understanding, and everything unfolds with an exasperated slowness, as if time itself had been boiled in a soup of nonsense. It is a scene that seems to come out of a Beckett opera ante litteram, yet it is perfectly faithful to the spirit of Carroll.

Sterling Holloway, who would later become famous as the voice of Winnie the Pooh, gives the Frog a shrill voice and a hopping gait, while Roscoe Ates, known for his comic babbling, turns the Fish into a bewildered messenger, more concerned with not tripping than delivering the invitation.

This brief interaction is a small jewel of physical comedy and linguistic nonsense, and in the 1933 film it becomes a theatrical parenthesis, a curtain that anticipates the chaos of the Duchess's kitchen and introduces Alice to a world where even official messages seem like sleight of hand.

HE SLEEPS

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.33 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Charlotte Virginia Henry e Polly Moran

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film, the Dodo is played by Polly Moran, a comedian known for her feisty and over-the-top roles. The choice to entrust the role to a woman in a character who has no defined gender in the book is already a surreal touch in itself, perfectly in line with the spirit of the film.

In the context of the story, the Dodo appears in the scene of the "caucus race", one of the most absurd and symbolic moments in Carroll's book. In the film, this sequence is rendered with a grotesque parade tone, where the Dodo leads a group of bizarre creatures in a race with no beginning and no end, no winners and no rules. His role is that of arbiter of the absurd, proclaiming everyone winners and handing out prizes at random, a perfect allegory of Victorian bureaucracy and politics.

Polly Moran

Pinterest.com

Polly Moran's costume is deliberately caricatured: a large beak, stiff feathers and a strutting, almost military gait. His voice is ringing, authoritarian, but also comically out of place. The Dodo speaks confidently, but says things that make no logical sense and for this very reason he becomes a ridiculous power figure, which Carroll used to satirize the social conventions of his time.

In the film, the scene is short but memorable: Alice watches, confused, as everyone runs in circles and the Dodo proclaims the end of the race with theatrical solemnity. It's a moment that perfectly embodies the tone of the film: choreographed nonsense, with a touch of social criticism disguised as feathers and pecks.

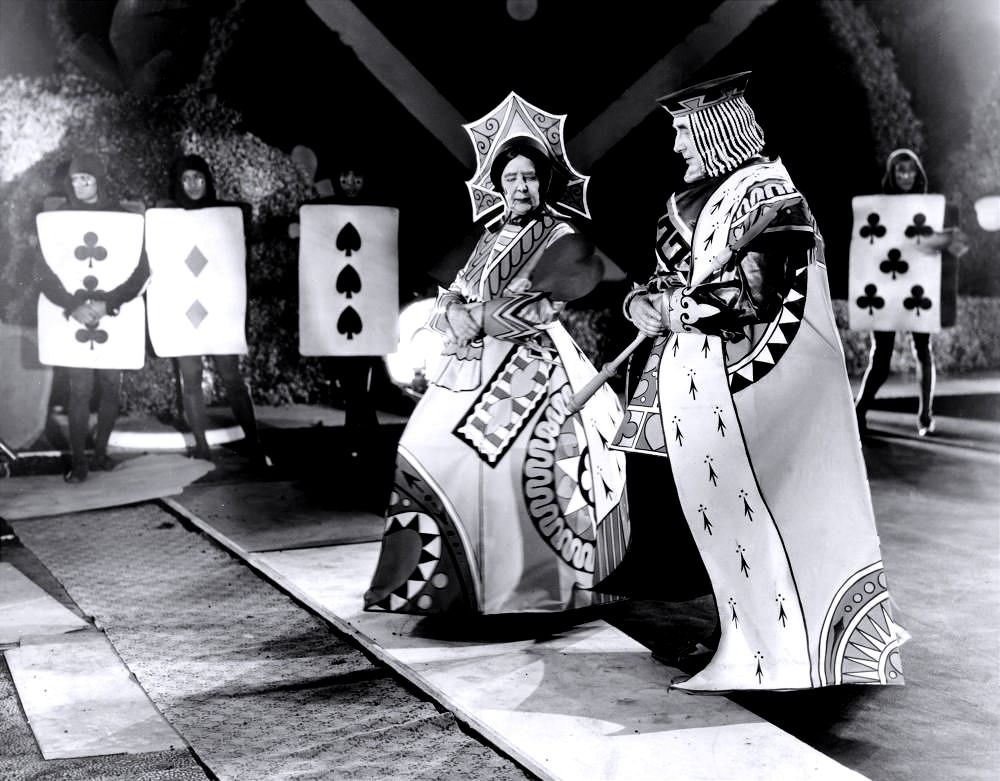

THE QUEEN, THE KING AND THE KNAVE OF HEARTS

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.22 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Card n.22 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

May Robson and Alec B. Francis

Pinterest.com

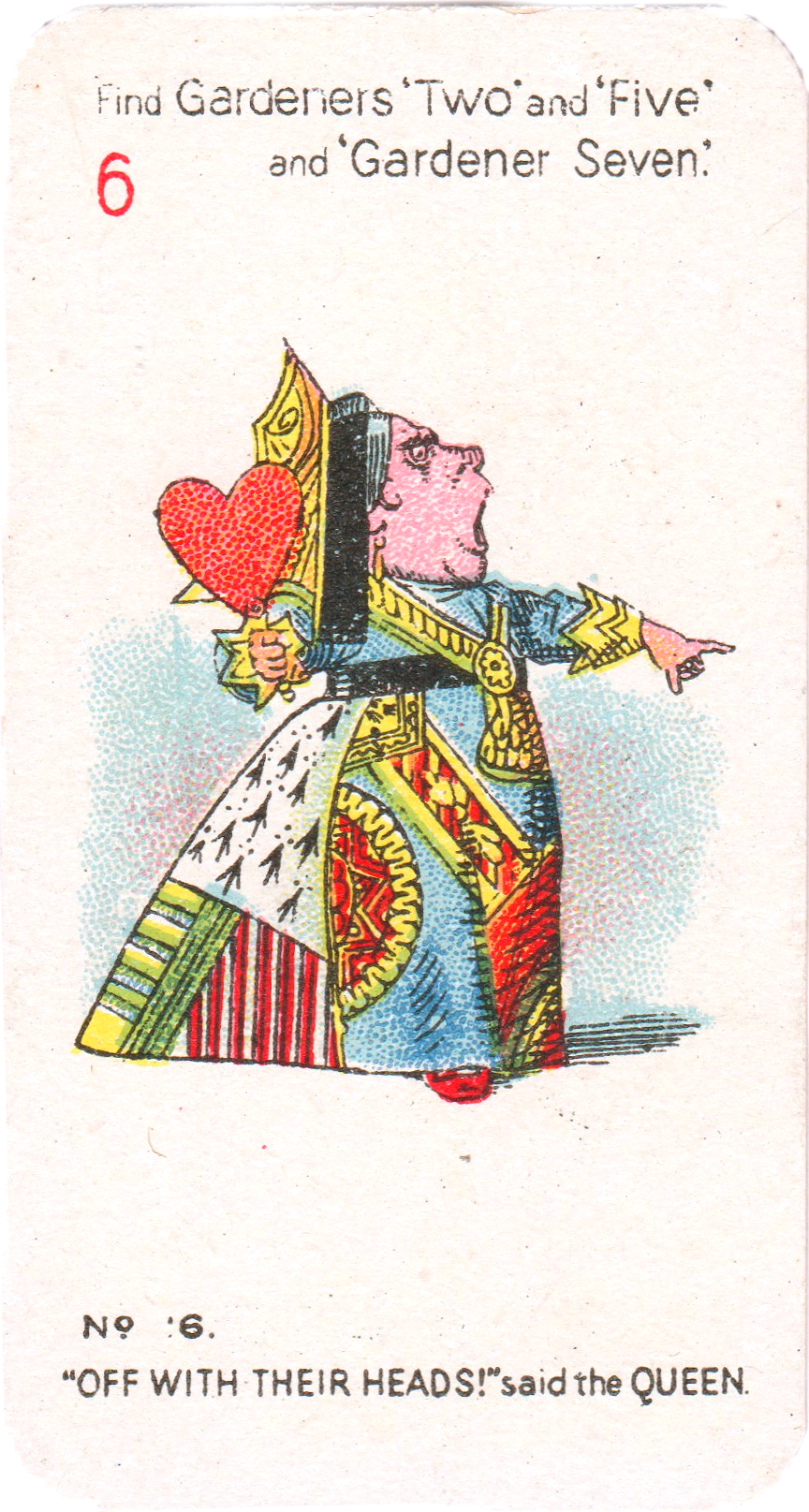

In the bizarre judicial carnival of the 1933 film, the Queen of Hearts and the King of Hearts reign as disjointed rulers of an illogical kingdom. She, furious and theatrical; He, meek and awkward. Together they form the perfect parody of Victorian power, suspended between theater and papier-mâché, where justice is just another rigged card game.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.6 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Playing the Queen is May Robson, an actress with imposing charisma and a voice as hoarse as a battle drum. Her costume is a triumph of red and gold: hearts everywhere, puffed sleeves, rigid crown and flaming gaze. Each of her appearances is an explosion of hysterical authority: "Off with her head!" becomes a mantra, a verbal tic, a weapon that transforms every contradiction into a sentence. Robson dominates the scene with operatic presence. His Queen does not listen, does not reflect: he orders, accuses, condemns. Yet, behind the excess, we can glimpse a ferocious satire of power that takes itself too seriously. It is the caricature of a sovereignty that has lost touch with reality and perhaps even with grammar.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.36 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Alongside her, Alec B. Francis plays the King of Hearts. His is a small, gentle, almost invisible character. He timidly tries to appease his wife's fury with stammering phrases and conciliatory gestures. She wears a disproportionate crown and a ceremonial dress that seems too great, a perfect metaphor for her role. During Alice's trial, he proposes a "small trial" before the sentence, but is immediately silenced. It is he who suggests leniency, who reminds us that Alice is only a child. He whispers justice in a world that screams for revenge, but his words are lost among cardboard-soldiers and disheveled decks.

Alec B. Francis e May Robson

Pinterest.com

Together, Queen and King are two aspects of the same fragile throne: she is the arbitrariness of power, he is his impotence. She screams, he mediates. She beheads, he barely scratches the surface of logic. They are chaos and compromise, noise and silence, shadow and flickering light of a realm where rules exist only to be subverted. In the 1933 film, this dynamic is represented with precision and irony: every scene involving them is a small act of theater of the absurd, where justice is a rigged deck and the throne is just a rickety stage.

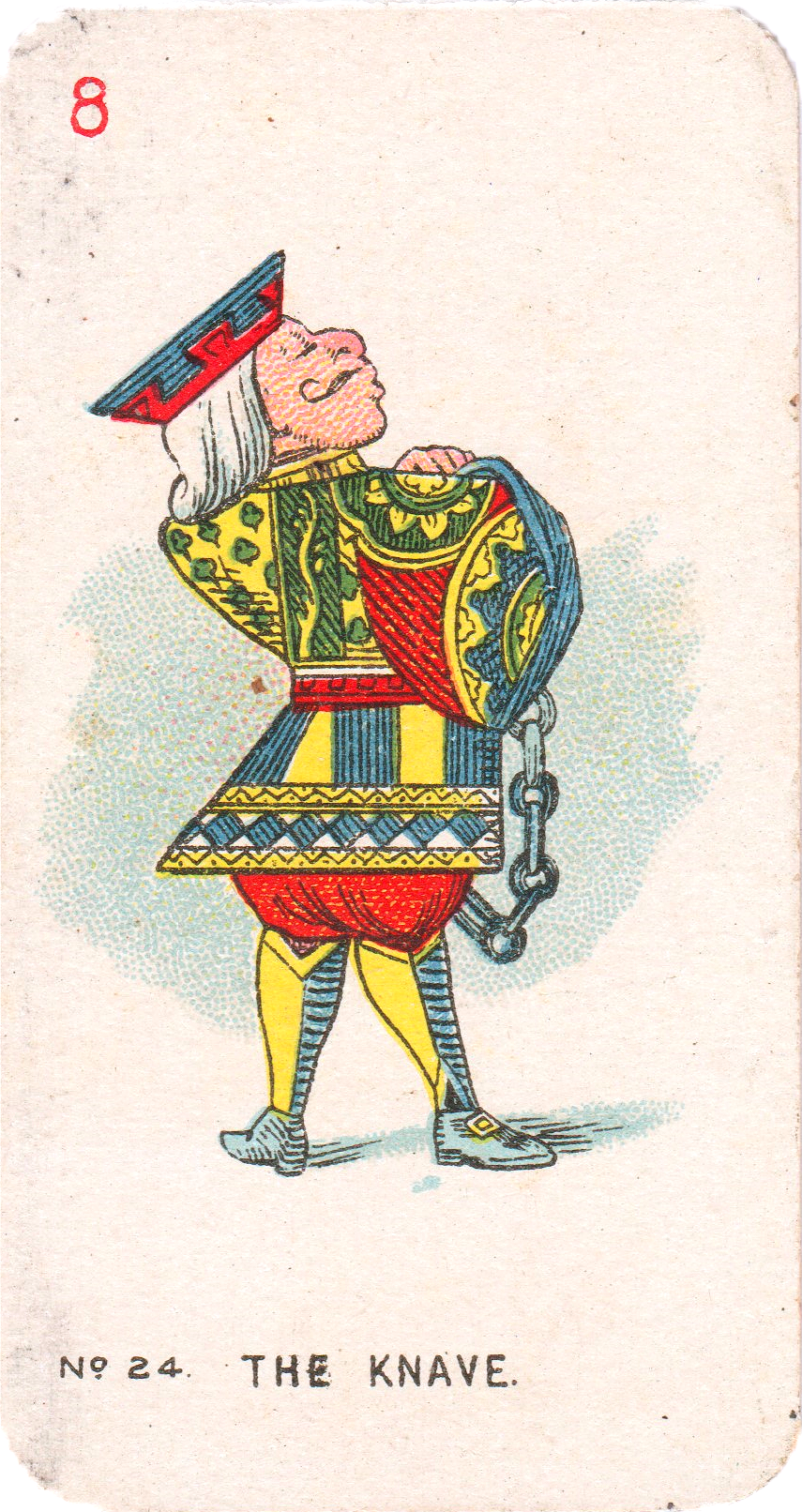

Card n.24 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

In the great card game that is Wonderland, the Jack of Hearts is the most fragile and ambiguous figure. Accused of stealing the Queen's tarts, he is the center of a trial that has already decided the verdict before it even began. Yet, paradoxically, he is also the character who speaks the least, moves the least, barely exists.

In the 1933 film, the Jack is played by William "Billy" Austin, an actor specializing in supporting and comic roles. His interpretation is deliberately modest: lowered eyes, rigid posture, perpetually confused expression. He wears a playing card costume that makes him almost indistinguishable from other soldiers, as if he had been chosen at random from the deck to be sacrificed on the altar of farcical justice.

During the trial, the Jack does not defend himself. He limits himself to denying in a feeble voice, while improbable witnesses are agitated around him: the Mad Hatter, the Duchess's Cook, even an anonymous note that no one knows who wrote. The King tries to maintain a semblance of order, but the Queen already shouts the sentence: "Off with his head!". The Knave remains there, motionless, the perfect scapegoat in a world where guilt is only a formality.

His narrative function is subtle but powerful: he is the sacrificed innocent, the symbol of a system that has lost all contact with logic. He is not a character to be remembered for what he does, but for what he suffers. And precisely for this reason, in his silent presence, he becomes one of the most tragic and modern figures in the film.

In the visual context of 1933, the Jack is also an element of contrast: while the Queen explodes in red and gold, and the King fidgets between parchments and proclamations, he remains white, flat, almost erased. It is the card that no one wants to play, but that everyone uses to prove that they have the deck in their hand.

Card n.23 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

And in that deck, one card deserves special attention: No. 23 in the Carreras series, titled "The Lawyers." At first glance it looks like a simple grotesque picture with three toga-clad birds... but looking closely at Tenniel's illustration, one discovers that those three feathered judges, seated at the bottom right of the tribunal in the trial against the Knave, are precisely the same ones portrayed in card no. 23 of the Carreras series." They wear togas, wigs, and watch impassively a scene that is already condemnation.

In front of them, on the trial table, even the infamous tarts appear: the same ones stolen by the Fante according to the prosecution. A piece of evidence as explicit as it is absurd, exposed as a dessert rather than as a forensic clue.

Carreras, with a theatrical eye, extrapolates that marginal detail of Tenniel's panel and transforms it into a nonsense legal miniature: three judging birds, tarts in evidence, and a mocking look at Wonderland justice.

Curiously, the actor who plays the Jack, William "Billy" Austin, also reappears later in the film under feathers and roars as the Griffin. It is an ironic and perfectly Carrollian metamorphosis: the accused and silenced man becomes a mythological creature, gruff and verbose, who guides Alice to the beach of the False Turtle. A double role that reflects the two extremes of nonsense: being erased and being over the top. Two characters, two masks, one dazed face of Wonderland

THE COOK

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.26 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Among the vapors and screams of the most senseless cuisine in Wonderland, a disjointed and dangerously homely figure wanders: the Duchess's Cook, played by Lillian Harmer. Hair in turmoil, filthy apron, ladle wielded like a cudgel, this Cook is more of a weapon of culinary destruction than a supporting character. In the 1933 film, she appears in one of the most claustrophobic and slapstick scenes: the Duchess's kitchen is a toxic place, full of smoke and screams, where pepper flies more than dialogue. Lillian Harmer, a character actress often associated with roles as waitresses, nurses and maids, here frees herself from any restraint and offers a physical, noisy and menacingly funny performance. He doesn't say much, it's useless: it's his movements, exasperated as in a cartoon, that tell everything. Every time Alice opens her mouth, the Cook throws something; Every attempt at logic is submerged by ladle blows, sneezes and pots bouncing off the walls. In the visual and symbolic context of the film, the Cook is an explosion of domestic chaos: she destroys the rules of good manners with the same ease with which she spills pepper in the soup. His presence suggests that even the home, a place of order and care, has become a grotesque trench in Wonderland. And while the Duchess holds a screaming child (who will soon become a piglet) in her arms, the Cook acts like a mad spirit of the hearth, violent, irrepressible, absurd. Harmer manages to make this tiny character a mad splinter in the great surreal mechanism of the film. Like the Hatter or the Queen, the Cook is also an extreme caricature, an overflowing cog in an already delirious machine. She is a culinary fury with an apron, a nurse who instead of curing, pounds, throws and spices everything with madness

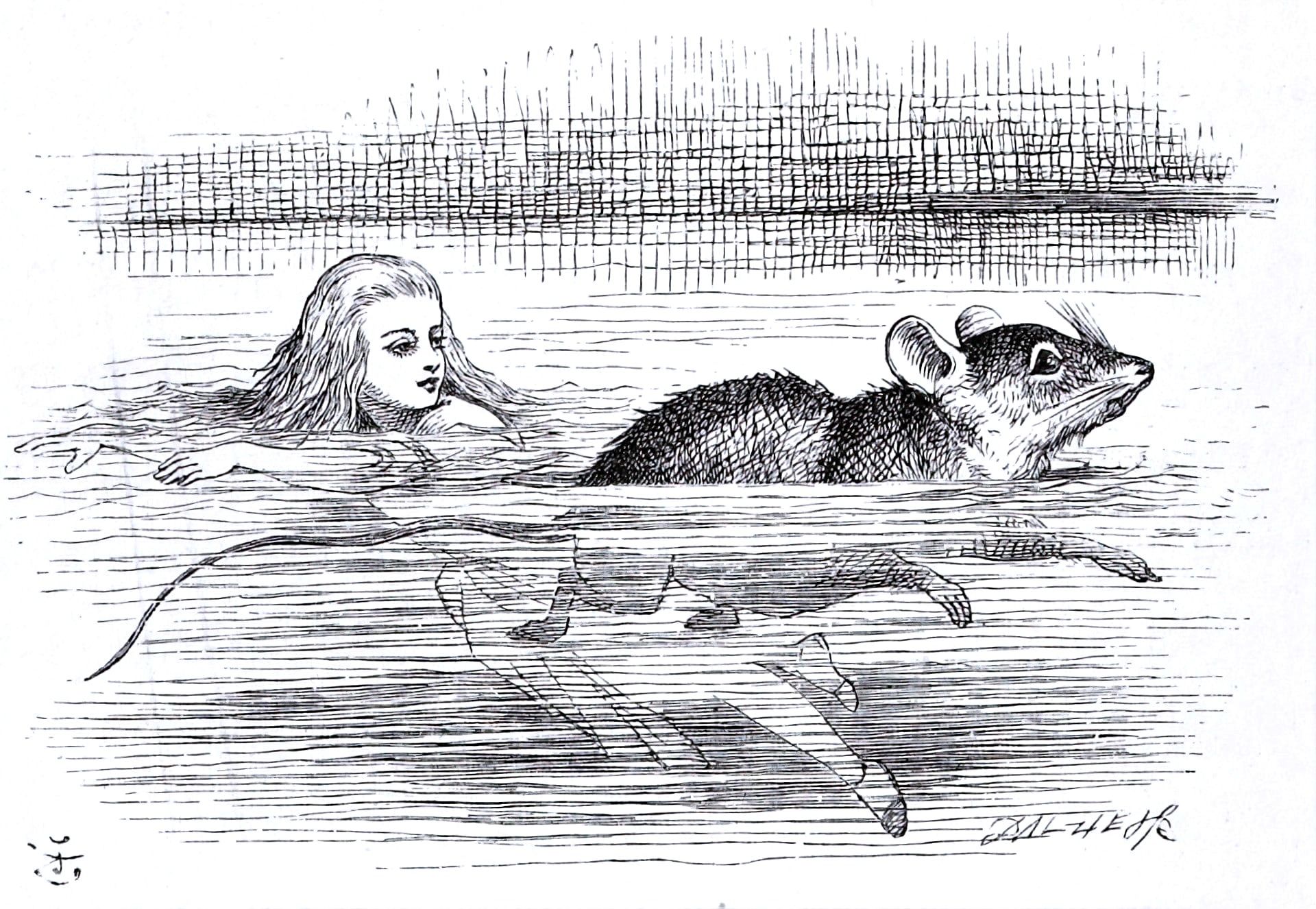

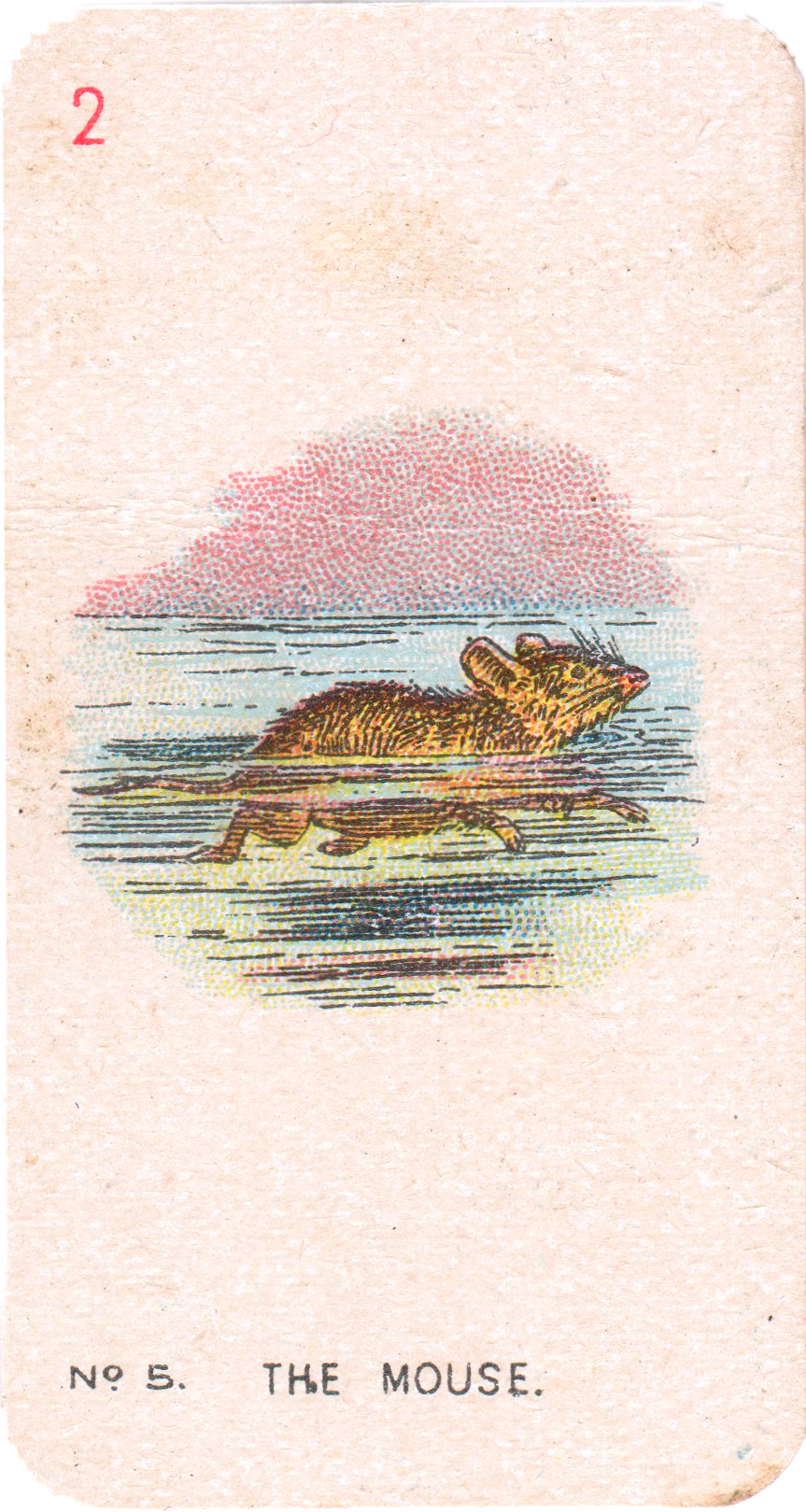

THE MOUSE

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.5 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

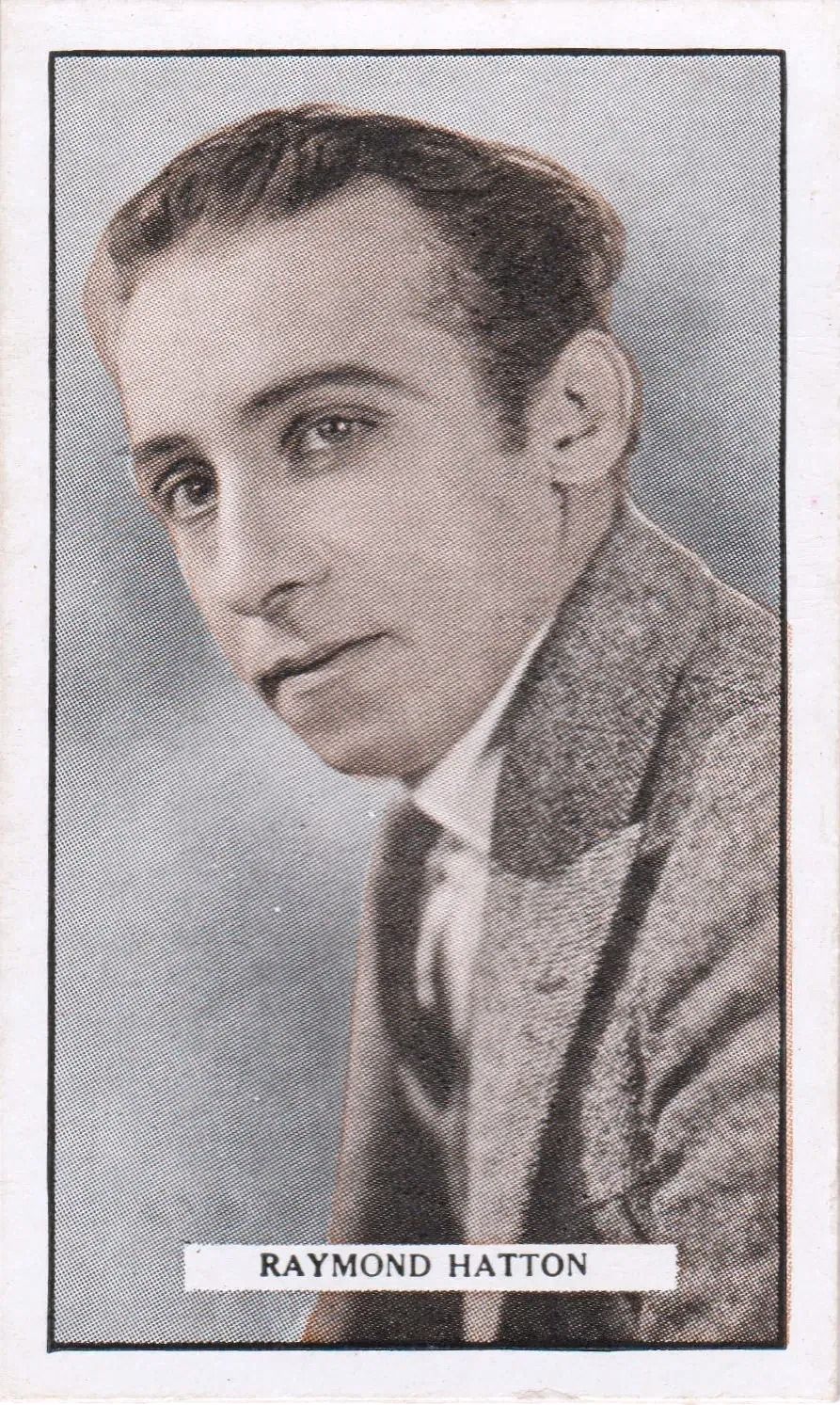

Charlotte Henry e Raymond Hatton

IMBD

In the salty sea of tears, among wet feathers and floating tails, a small, offended and tremendously touchy figure emerges: the Mouse. His appearance is brief, but full of that surreal melancholy that runs through the entire first part of the 1933 film.

Card n.67 CINEMA STARS

GALLAHER LTD (1926)

(personal collection)

Played by Raymond Hatton, a veteran actor of silent and sound cinema, the Mouse is a creature that seems to have come out of a Victorian courtroom, with its gentleman's suit and the stern gaze of someone who has already seen too many absurdities to be amazed again.

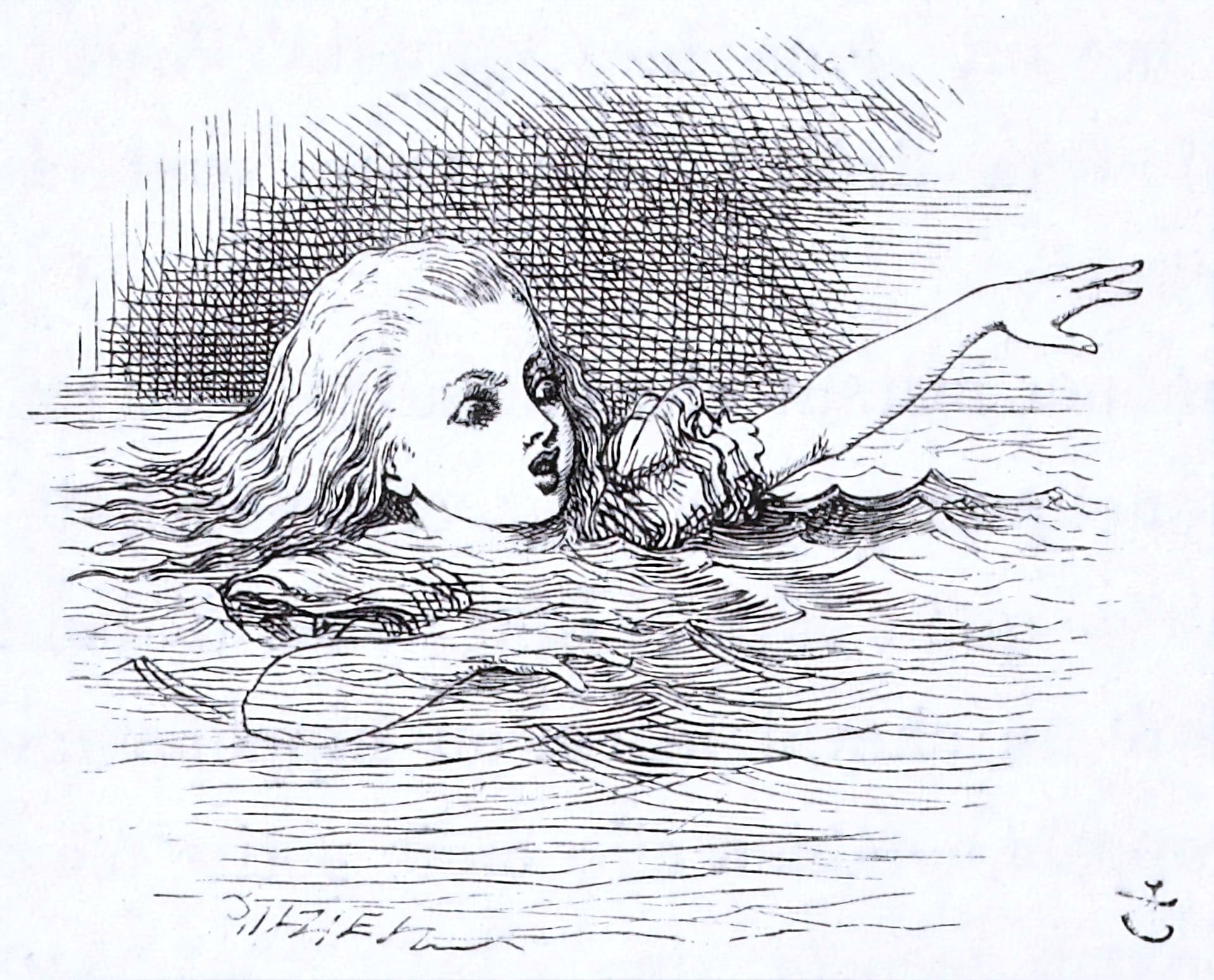

In Carroll's book, the Mouse is the first character with whom Alice tries to establish a rational dialogue but fails miserably. In the film, this dynamic is maintained with grace and irony: Alice tries to console him, but ends up offending him with a comment about mousetraps. In that scene, immersed in waves and wet feathers, the image of Alice swimming in the pool of tears restores the fairytale absurdity of the moment.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.6 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

The Mouse walks away indignantly, leaving behind a trail of wounded dignity and wet mustache.

Raymond Hatton, with a rodent-made face and a slightly nasal voice, manages to make the character more human than animal. It is a Mouse that does not run, but walks with an indignant step; he does not squeak, but argues. His interpretation is all played on subtle shades of sarcasm and resentment, as if the Mouse were the only inhabitant of Wonderland to realize the absurdity that surrounds him and not to find it funny at all.

The costume is simple but effective: big ears, pointed muzzle, and a little bureaucrat outfit of nonsense. Hatton, who in his career had played cowboys, mad scientists and saloon criminals, here turns into a creature offended by grammar and logic, perfectly at ease in a world where tears become oceans and words are confused with tails.

The Mouse never returns in the film, but his brief appearance leaves an echo: he is the first character to show Alice the emotional fragility of the inhabitants of Wonderland, and perhaps even their humanity hidden under masks and furs.

Roses to paint, Heads to cut

Cards at the service of the Queen of Hearts

Charlotte Henry, May Robson e Alec B. Francis

IMBD

In a kingdom where the red of roses is law and verdicts rain down without trial, even a playing card can become executioner or servant. Some brush lies on the wrong petals, others raise axes on the sovereign's orders. They are the low cards of Wonderland, apparently secondary but central pieces in the staging of capricious power. This is their story.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.17 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Card n.18 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Drawing of the scene from the Movie - Charlotte Henry and Billy Bevan

(Copilot AI)

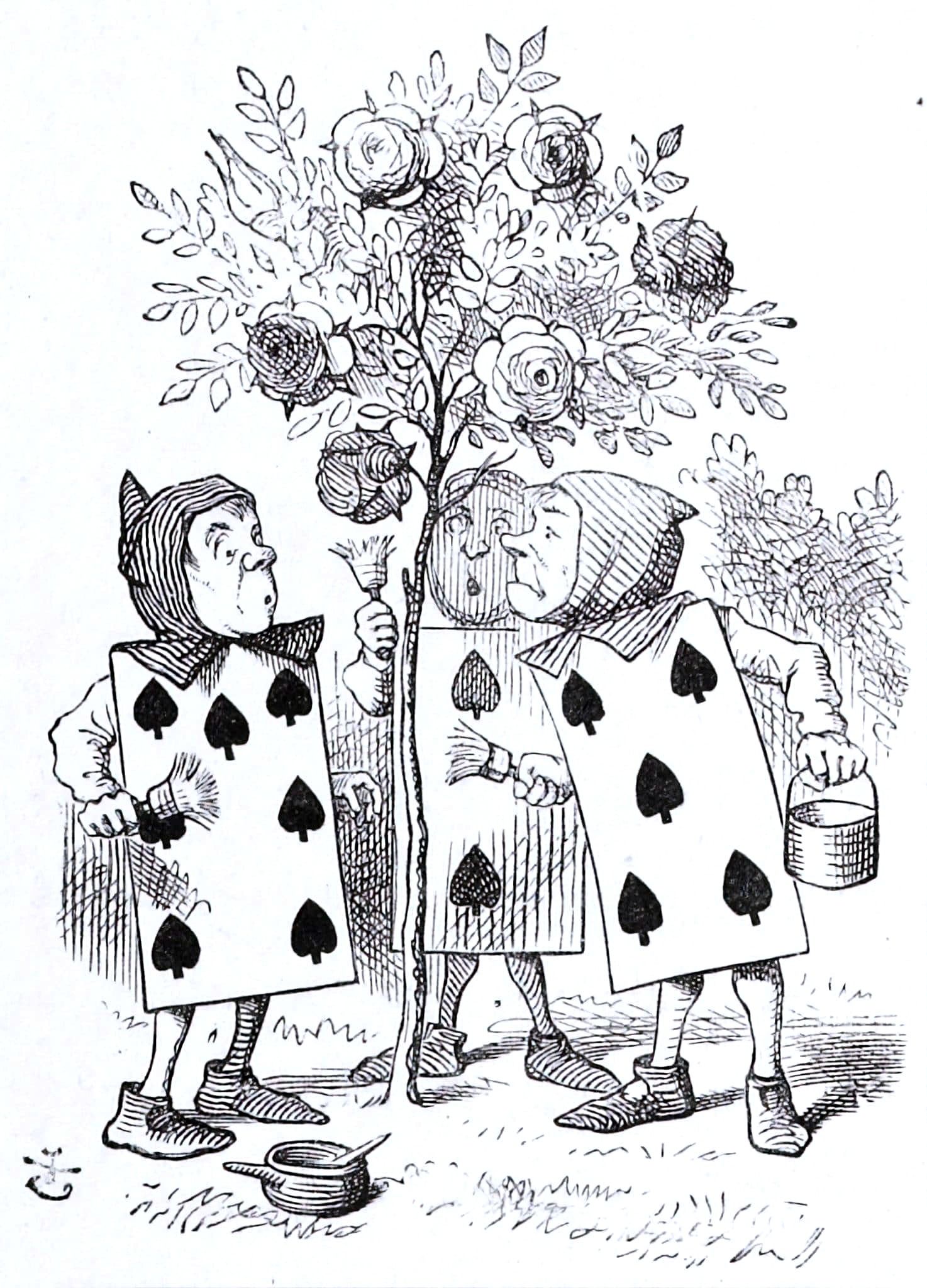

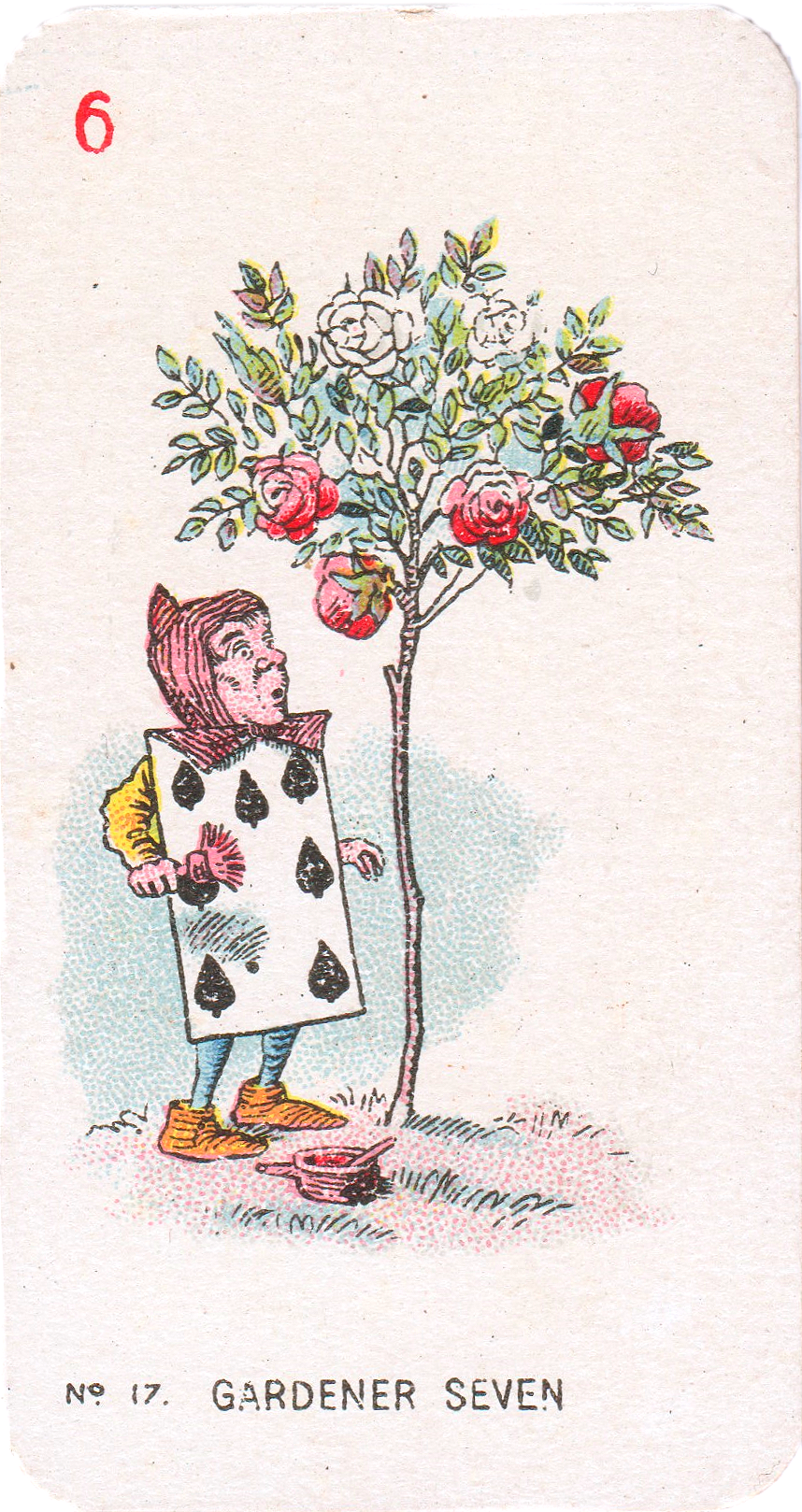

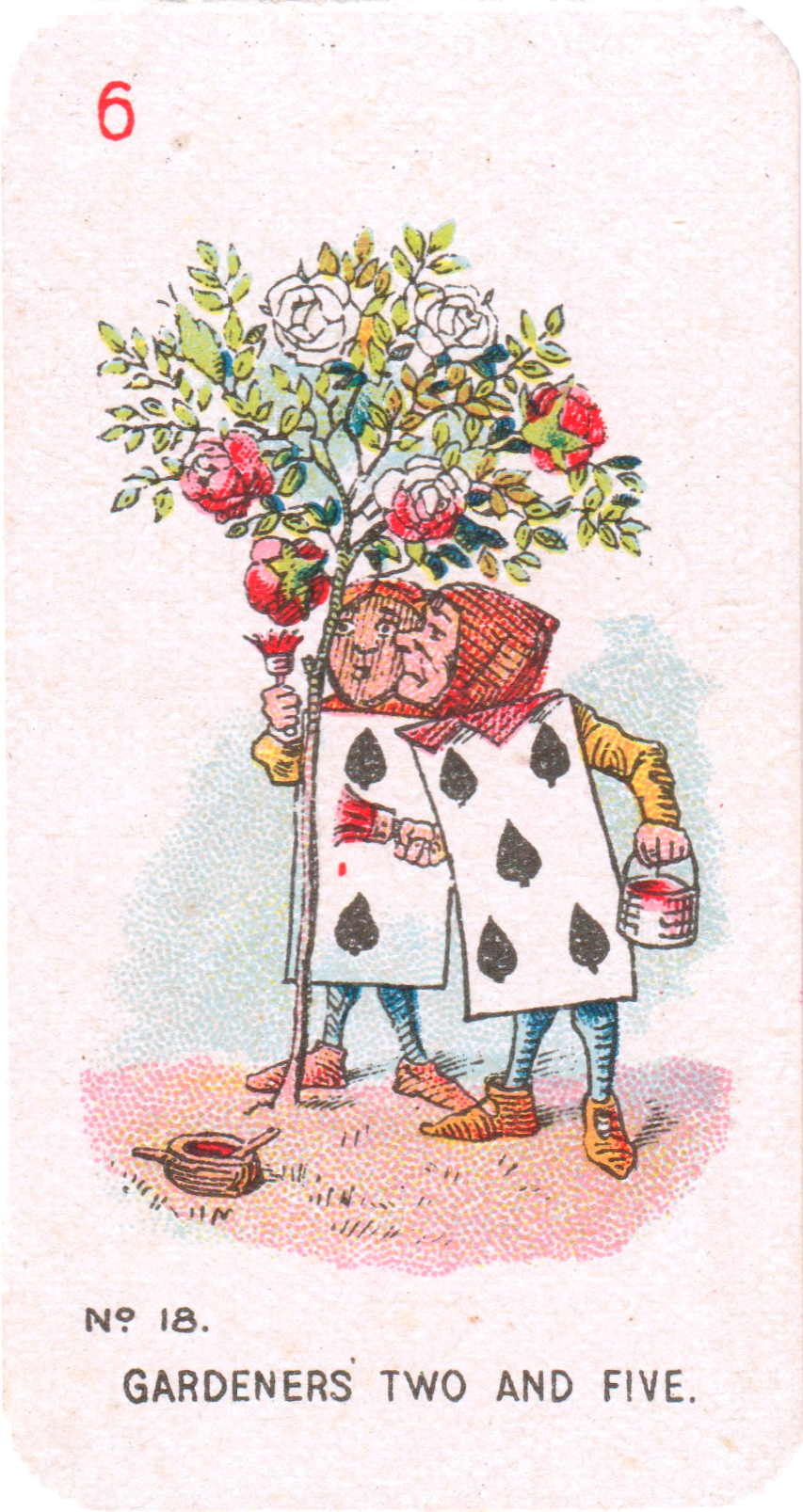

It all begins in the Queen's garden. A bush of white roses stands where red roses should be. Fatal mistake. Three gardeners the Two, the Five and the Seven of Spades are intent on painting the flowers with red paint, in a desperate attempt to mask the botanical offense. It is the most parodic and tragic episode of Carroll's nonsense: painting as a royal lie, appearance as the only truth admitted.

In John Tenniel's illustrations, the three appear with hoods, buckets and brushes in their hands. They look like medieval servants disguised as cards, and move bent under the weight of royal terror. In the Carreras series (1930), two figurines immortalize this moment: one depicting the Two and the Five together, another dedicated to the solo Seven. Details such as the dripping paint, the folds of the caps, the awkward poses: everything recalls the original design with impressive fidelity.

These papers never raise their voices. They do not challenge. Simply, they try to correct the error by following illogical orders. They are the essence of parodic servility, yet precisely for this reason unforgettable.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.34 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

But the deck also has its executioner. In the scene of the final trial, when the Queen shouts "Cut off his head!", a different card-figure appears: the Ace of Clubs, in the guise of the Headsman. Tenniel represents him standing, rigid, with a flat red hat and a dark veil on his face, which erases any identity. It has no expression, it has no name. Only a role to be fulfilled.

His line has gone down in history:

"I'm not going to behead nobody with heads like those — they haven't got any shoulders!"

A logical-anatomical protest that short-circuits the court. Justice falls, not by conscience, but by the anatomy of the papers: simply, you cannot cut off what has not been drawn.

The Carreras Figurine No. 34 crystallizes this moment. The character holds an axe, wears a red uniform and has his face obscured by the same dark veil seen in Tenniel's illustration. It is one of the most evocative of the set, because it carries the idea of blind, mechanical and impersonal justice. The choice to represent him as Ace of Clubs, when the gardeners were of Spades, suggests a clear separation: the executioner is not one of them. It's something worse.

In the 1933 film, directed the kingdom of cards takes tangible shape. Scenes from the garden, the trial, the court: everything is populated by figures in playing card costumes, taken with almost philological fidelity from Tenniel's tables.

Richard "Skeets" Gallagher, Charlotte Henry, Alec B. Francis e May Robson

IMBD

In an archival frame, Alice appears next to the King, Queen and Herald, while behind him stand not one, but three identical Aces of Clubs, with dark hats and covered faces. They are a host of executioners, mute and motionless as statues. It is a powerful visual choice: multiplying the perpetrator erases the individual, transforming justice into a replicable function, into a silent chorus of royal terror. None of the three speaks. No one has a distinguishable face. Everyone is a weapon without will.

The costume as far as we can see still follows the lines dictated by Tenniel and anticipated by the Carreras figurine. Cinema takes up, reworks and strengthens symbolism: where Carroll ironically made fun of an awkward executioner, the film multiplies his shadow, making him an institution rather than a character.

In a deck where noble titles seem to concentrate all power, it is often the number cards that hold the scene. With dripping brushes, roses to correct, axes to hold and silences to guard, they are the silent bearers of the upside-down logic of Wonderland. And if a stain of paint is enough to trigger a conviction, perhaps it is appropriate to take a good look at every card that passes through our hands. Because even the Two of Spades can become an involuntary accomplice of a botanical lie or the last witness behind the executioner's veil.

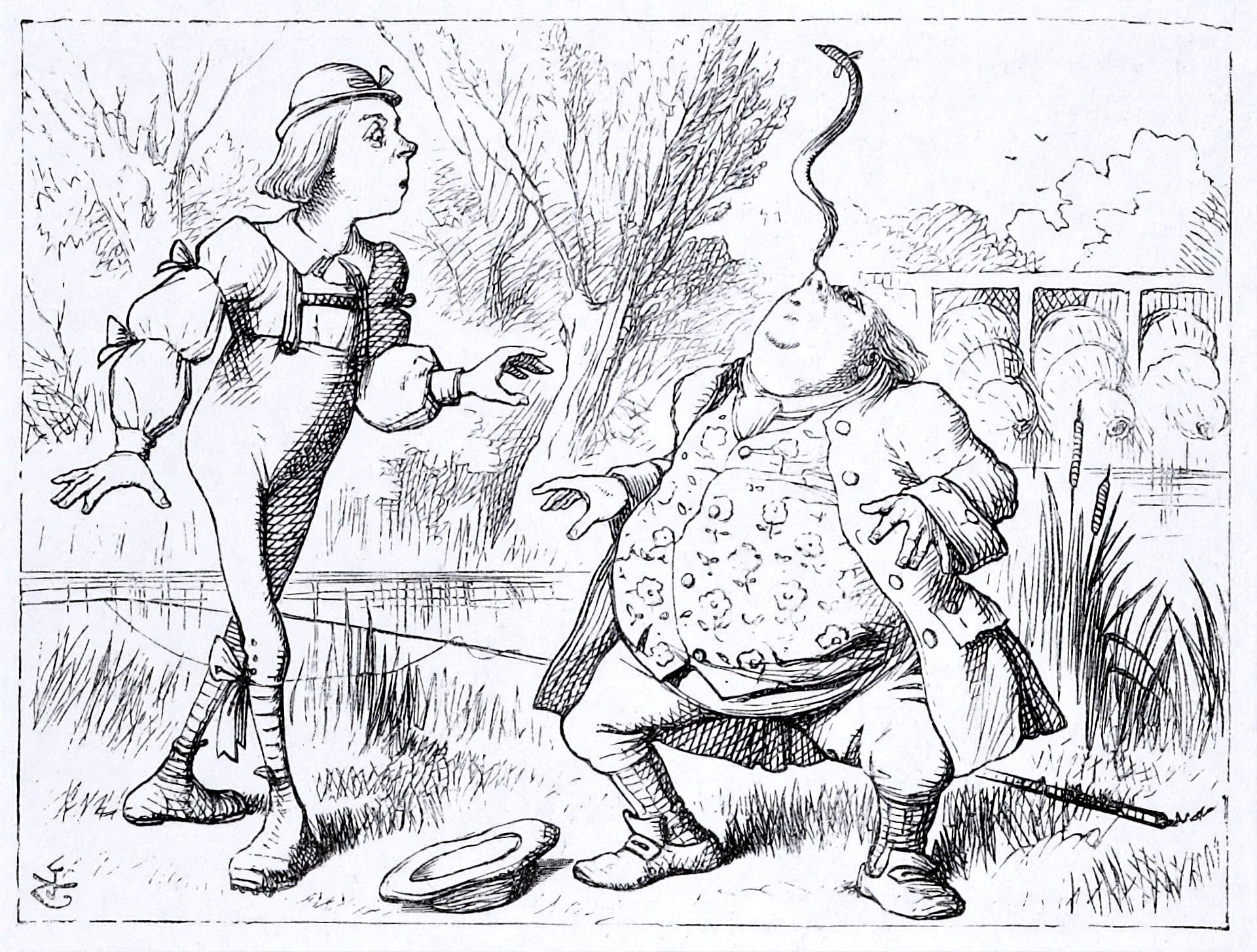

You are old, Father Guglielmo...

An upside-down poem, two redeemed figurines

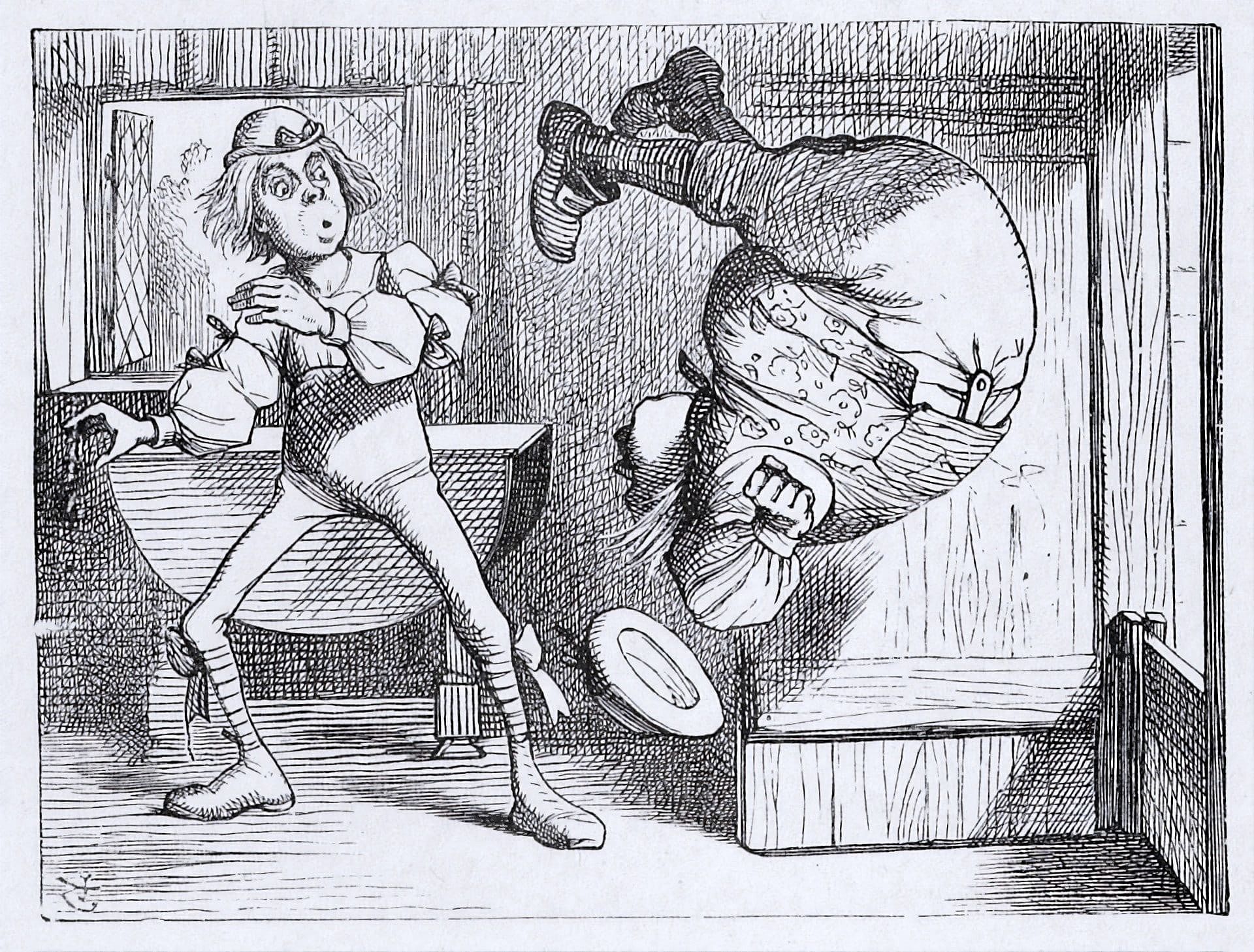

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

In the reasoned chaos of Wonderland, even poetry becomes a parody and ironic reflection of Victorian morality. Carroll knew this well, when he made Alice recite the distorted verses of a family nursery rhyme at the request of the Caterpillar. Thus was born You Are Old, Father William, a surreal dialogue between a zealous young man and an agile, mocking old man, capable of standing vertically as no tutor would approve.

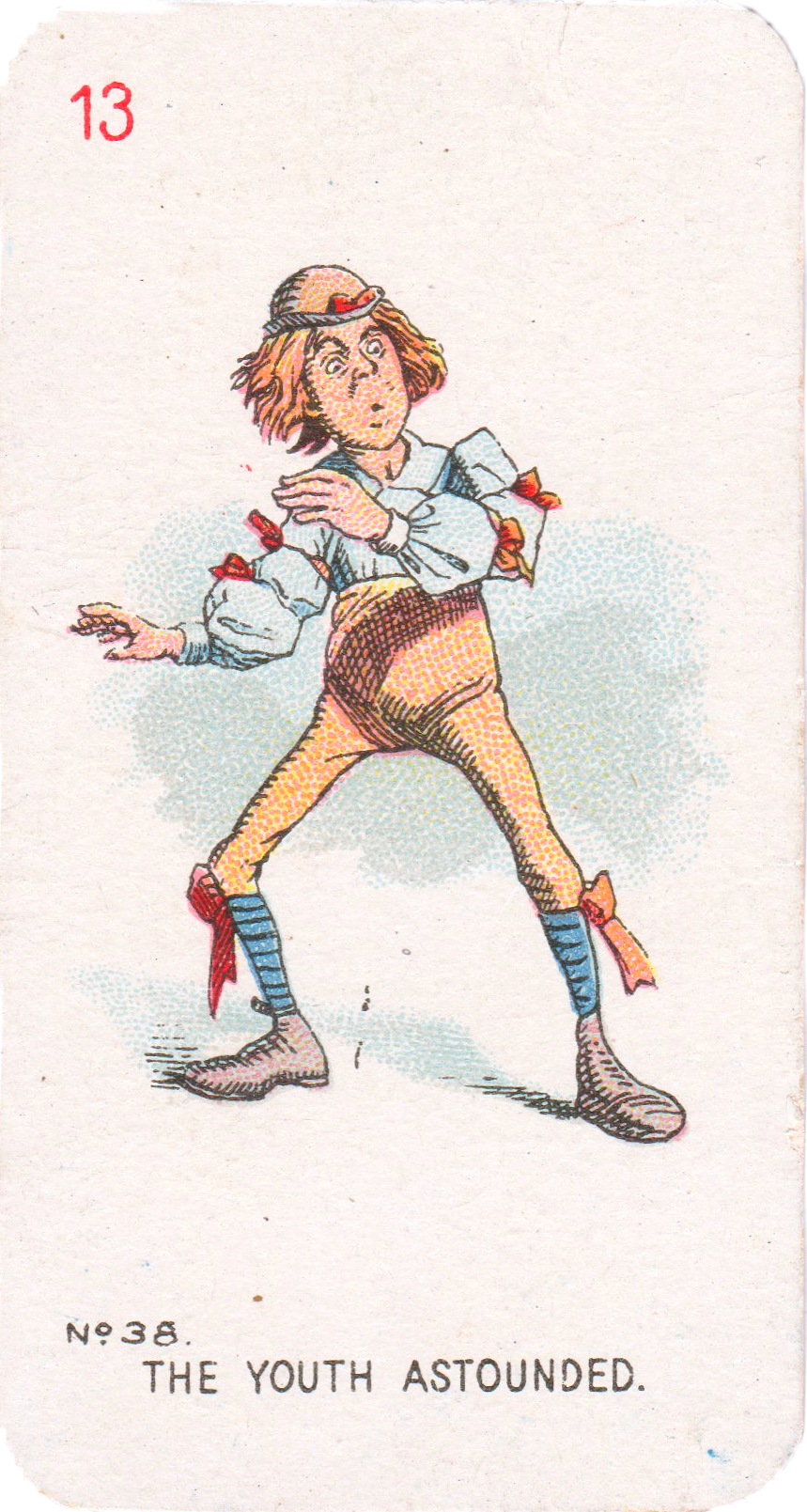

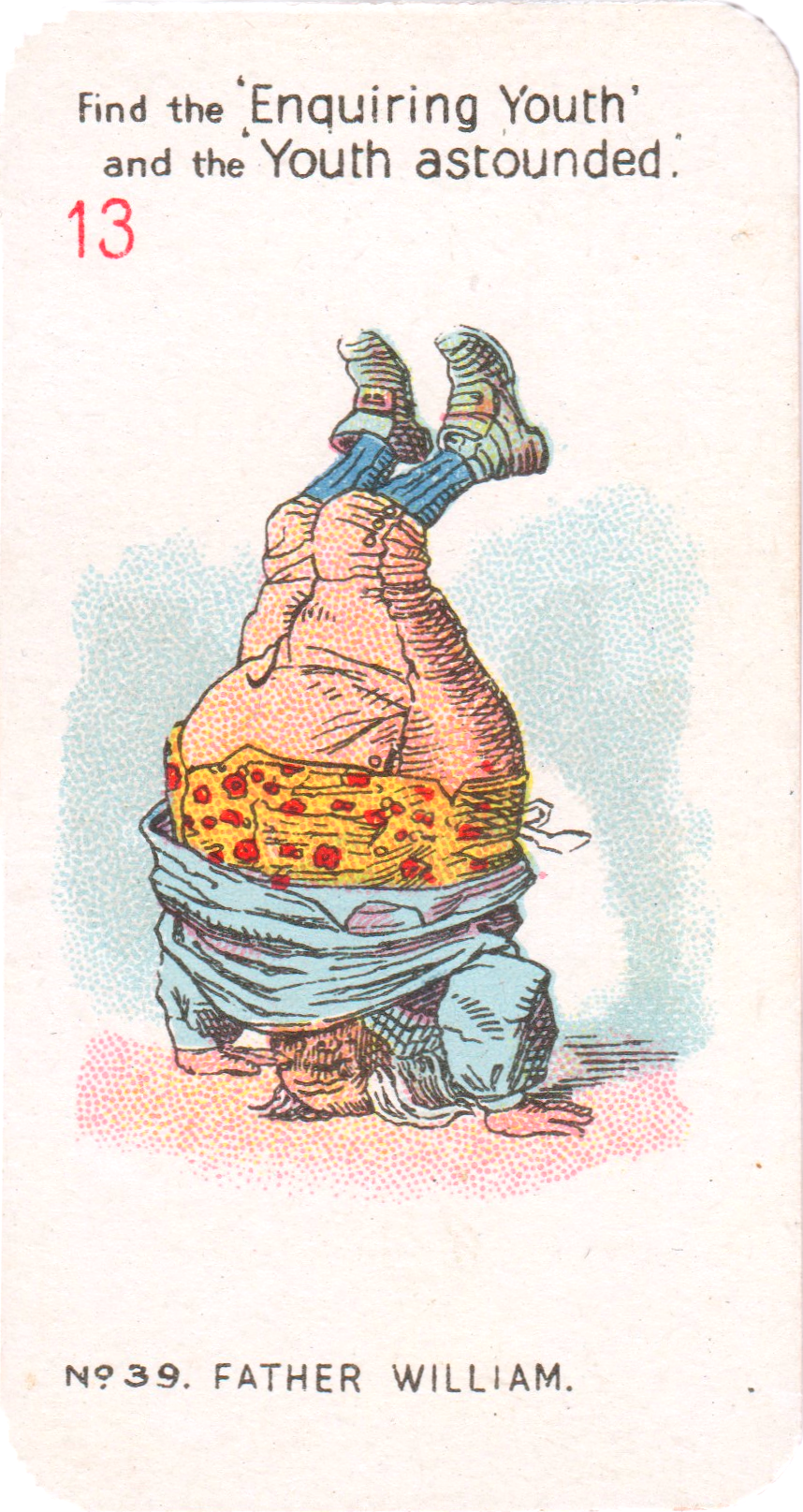

Carreras figurines dedicate three theatrical portraits to this scene or, rather, to this scenic poetry. But instead of representing everything in a single image, they decide to break down the narrative and transform it into a small collector's triptych, like a miniature comedy curtain.

Card n.37 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

The young moralist appears in a firm and proud pose, dressed in red and purple. It holds a two-pronged hay fork, a symbol of rural rigor but also of a self-invested authority. The expression is that of someone who asks questions not out of curiosity, but to affirm his own presumed wisdom. The scene faithfully recalls Tenniel's illustration in which, in a field among the sheaves, the boy addresses the old man in an inquisitive tone.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

Card n.38 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

A moment later, everything turns upside down. The young man is stunned, displaced, his hands raised in a theatrical gesture. The scene is inspired by a second illustration by Tenniel, set in a domestic interior, where Father William performs an acrobatic somersault that short-circuits every rule. The boy does not understand, and his grimace is the real climax of nonsense.

Card n.39 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

Finally, here he is: the old man turned upside down, an impassive acrobat. She wears bright clothes, and her trousers drop just enough to break the decorum. He is the embodiment of nonsense elevated to art. The map cites the same illustration from which no. 37 was born, but on its own, it makes a close-up, almost cinematic shot.

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film Alice in Wonderland, neither Father William nor the Young Man appear explicitly. The poem is not recited, no somersault or balanced eel finds space on the screen. Nevertheless... their spirit hovers.

This can be sensed in the excessive mimicry of certain characters, in the surreal exchanges that recall the poetic question and answer and in the glances in the camera that seem to say: "Did you really understand what you saw?"

Carreras stickers fill this void. They give voice (and legs in the air) to a poetry that remains in the background in the film. And they remind us that, in Carroll's world, what is missing is not always really absent. Sometimes you just have to turn the paper over.

Voce narrante: Erik J. Szesko (LibriVox)

Bill's flight (which the film forgot)

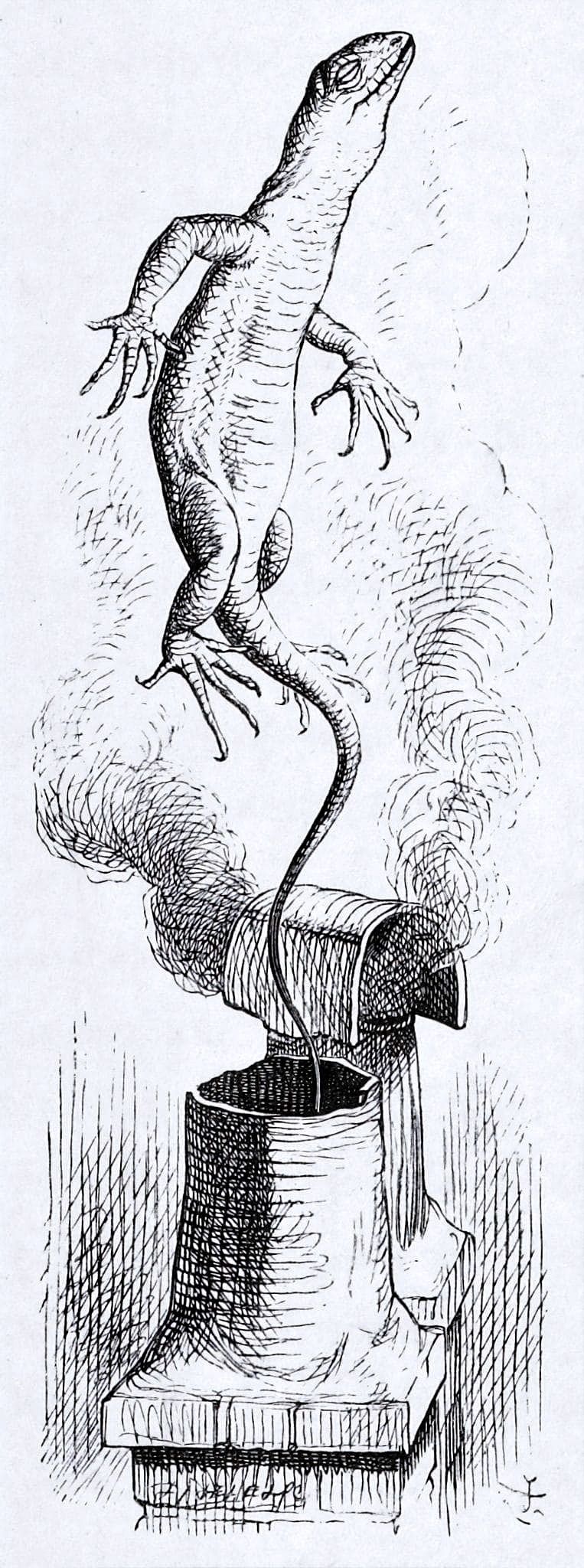

John Tenniel`s original (1865) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Alice in Wonderland"

Pinterest.com

There is a moment, in the 1933 film Alice in Wonderland, when a character is expected to enter. He is not a famous name, he does not have memorable lines, but those who know the book well look for it with their eyes: Bill the Lizard.

Yet, it never comes.

No stairs, no chimney, no cloud of soot: the character in the book and immortalized in at least one figurine of the Carreras series is omitted with a sharp cut, and with him disappears one of the most slapstick, absurd and mechanically perfect scenes of Carrollian nonsense.

Card n.30 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

But his absence on the screen allows us to tell him better, just as we would do with a theatrical supporting actor who leaves the scene before his time. Carroll, Tenniel and, above all, Card n.30 of the Carreras game take care of collecting the traces.

Card n.10 - Alice in Wonderland -CARRERAS Ltd. (1930)

(personal collection)

It all begins, of course, with a small bottle. Alice, who has recently fallen into the underworld, finds a vial with "DRINK ME" written on it. The Carreras figurine that illustrates the scene is a small theater of doubt: Alice lifts the object as if she knew that nothing, from that moment on, will remain motionless. Drink. It gets smaller, then it grows, then it gets smaller again... until, grown out of proportion, she gets stuck in the White Rabbit's house with one arm out of the window and one foot in the fireplace.

The Rabbit, in a panic, calls for help. Bill enters the scene, the worker lizard, summoned to climb the roof and solve the problem "from the chimney". He doesn't ask questions. He takes the ladder, climbs, and is thrown out of the chimney by a giant foot that does not even know it has hit him. It circles through the air like a Christmas rocket and disappears, leaving behind only a trail of ash, a broken ladder and a half-muffled laugh.

The Carreras figurine that portrays him is perfect in this: The background is simple, everything is focused on the suspended moment of the action. No scales, no caricatures: it is a faithful synthesis of the iconic detail that Tenniel entrusts to the table of the chapter "The Rabbit Sends in a Little Bill".

This figurine, rather than reinventing, crystallizes the moment in which Bill's parable reaches its narrative and physical peak: out of the fireplace, off the scene, out of control. Unlike the film that ignores it, paper celebrates it. In a few square centimeters it tells an entire scene, a narrative explosion in miniature.

In the book, Bill disappears after that flight. No one mentions him anymore. He is a use-and-throw character, built for a precise moment of physical and surreal nonsense. The 1933 film, with its severe stage choices, decides not to even let him enter the scene.

But the revenge will come eighteen years later. In the 1951 Disney animated film, Bill returns, or rather flies. He speaks with a cockney accent, climbs onto the roof reluctantly, and is literally pushed down the chimney by the Dodo. The rest is smoke, soot and cinematic glory. Finally, the character kicked out of the narrative finds a place in the visual canon of Alice's world and makes an entrance/exit that is worth as much as a thousand lines.

And so, from a staircase that did not reach the top and a chimney that did not want to be walked, one of the most memorable characters among the forgotten ones is born. Where the film is silent, the sticker speaks. And in that small reptile thrown into the air suspended between paper, ashes and irony remains the sooshiest sign of nonsense.

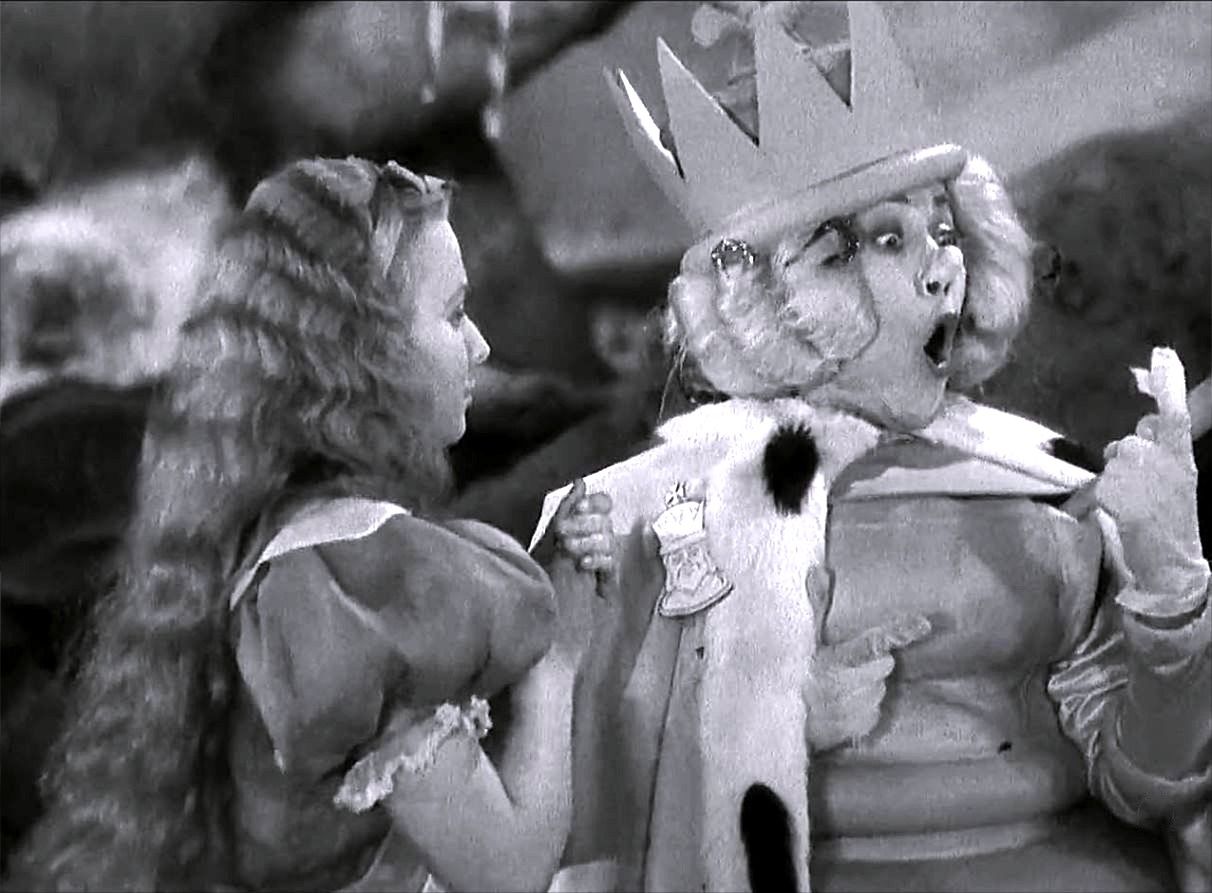

Rules don't exist

"Alice in Wonderland (1933)" from "Hollywood" magazine, January 1934

In Wonderland, the impossible is the rule. But when Alice crosses the mirror, the rules not only disappear: they are refracted, bent, made into theater. This is what happened in 1933, when cinema decided to stage not only the pages of Alice in Wonderland, but also those of Through the Looking Glass, Lewis Carroll's second book, published six years after the first. The film, however, does not declare it. No voice announces it, no caption explains it. And yet it does. With surreal grace, he inserts characters that Alice should have met only after the journey between the chessboards: quarrelsome twins, talking eggs, out-of-tune knights and creatures from British nursery rhymes.

It is a daring cinematic gesture, which betrays the text but not the dream. Because in nonsense, time is not linear, and apparitions do not respect boundaries. Paramount directors choose the face of Gary Cooper to play the White Knight, W.C. Fields to embody Humpty Dumpty, and two slapstick comedians to give body to Tweedledum and Tweedledee. None of them should have appeared in the first book. And yet there they are, on the screen, between the Queen of Hearts and the White Rabbit, as if the second volume had been disassembled and recombined in the first.

It is as if the film itself were a dream within a dream: no longer a faithful transposition, but a secret combination between two contiguous worlds. And the result is an adaptation that makes the invisible visible, where the chessboard is shuffled with the cards, and the two queens, the Red and the White, sip tea in the same living room, without knowing that they belong to different narrative universes.

In this section, we will delve right there: into the deception of time, among the "off-the-book" characters that the 1933 film made memorable. These are not mistakes, but poetic choices. And if Carroll taught us anything, it's this: in Wonderland, fidelity to logic is not required. Because, after all, the rules do not exist.

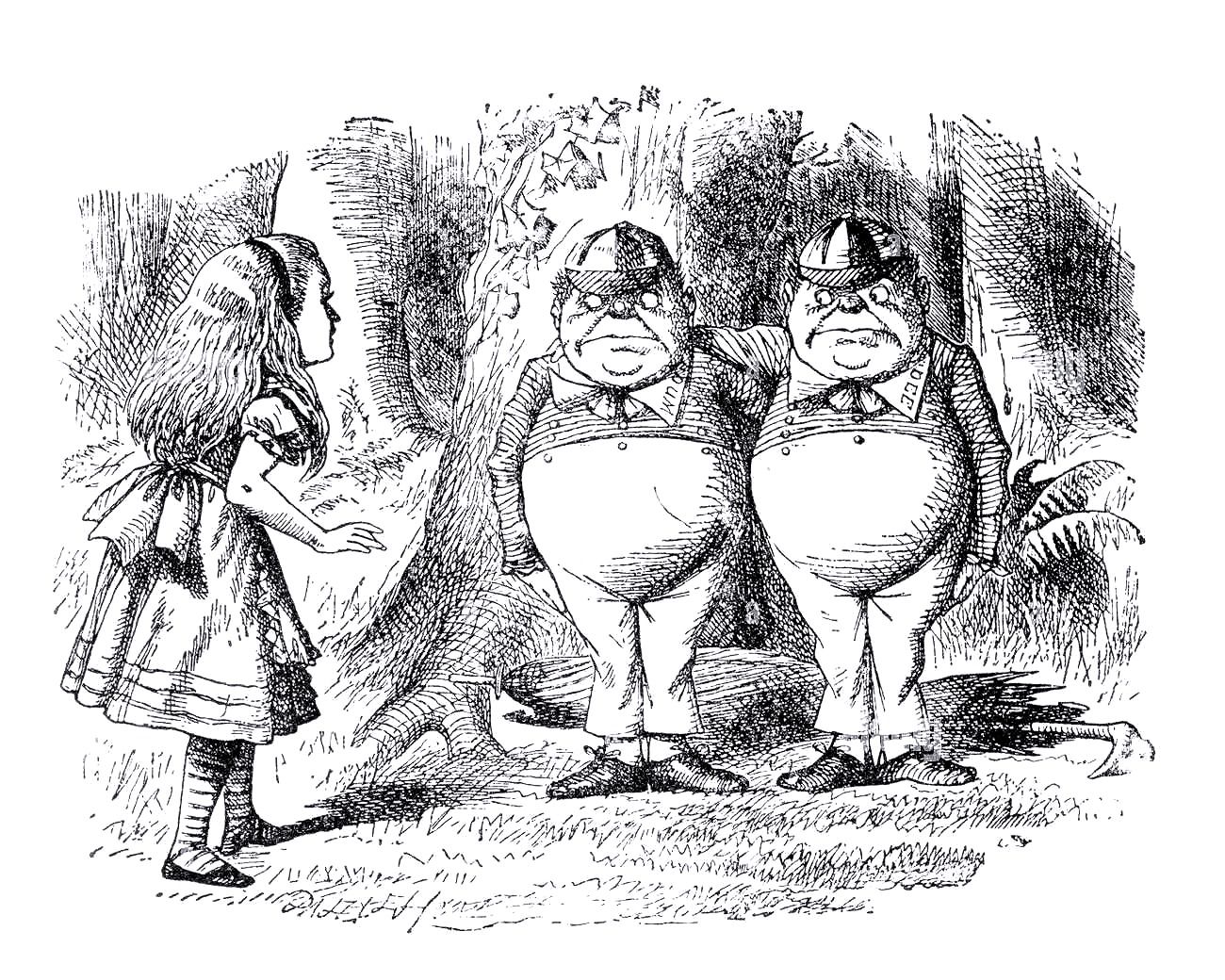

Tweedledum e Tweedledee

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Roscoe Karns e Jack Oakie

Pinterest.com

In the book Through the Looking Glass, Alice meets them in a clearing that looks like something out of a nursery rhyme and in fact it is. Tweedledum and Tweedledee challenge each other for a broken rattle, chase each other without running, and speak with a logic that sounds like a polite lie. Illustrated by Tenniel with the proportions of Victorian puppets, they are the portrait of the useless, symmetrically absurd quarrel.

In the 1933 Paramount film, the twins appear even though they do not belong to the first book at all, and they do so with an overwhelming stage presence. To play them are Jack Oakie and Roscoe Karns, two actors from slapstick comedy, perfect for transforming nonsense into visual prank. Their scene is a grotesque ballet, a missed duel, a fragment of comic theater implanted in the White Rabbit's garden. There is no rattle, no crow, no clearing and yet there is the same playful tension, the one that makes nonsense a refined form of theater.

It is one of the many moments in which the '33 film mixes the two volumes without warning, drawing from Through the Looking Glass because certain characters simply could not be left out. The twins, in their restless symmetry, are too strong visually, too theatrical not to be summoned. And so there they are: between the Queen of Hearts and the Mad Hatter, as if the narrative line was just advice to be ignored.

In the film, their quarrel becomes almost a vaudeville choreography, with exaggerated movements and puffy clothes, but always in secret and magnificent dialogue with Tenniel's illustrations. It's Carroll reimagined for the big screen. Not a betrayal, but a variation on the theme. And in the world of wonders, you know: rules do not exist.

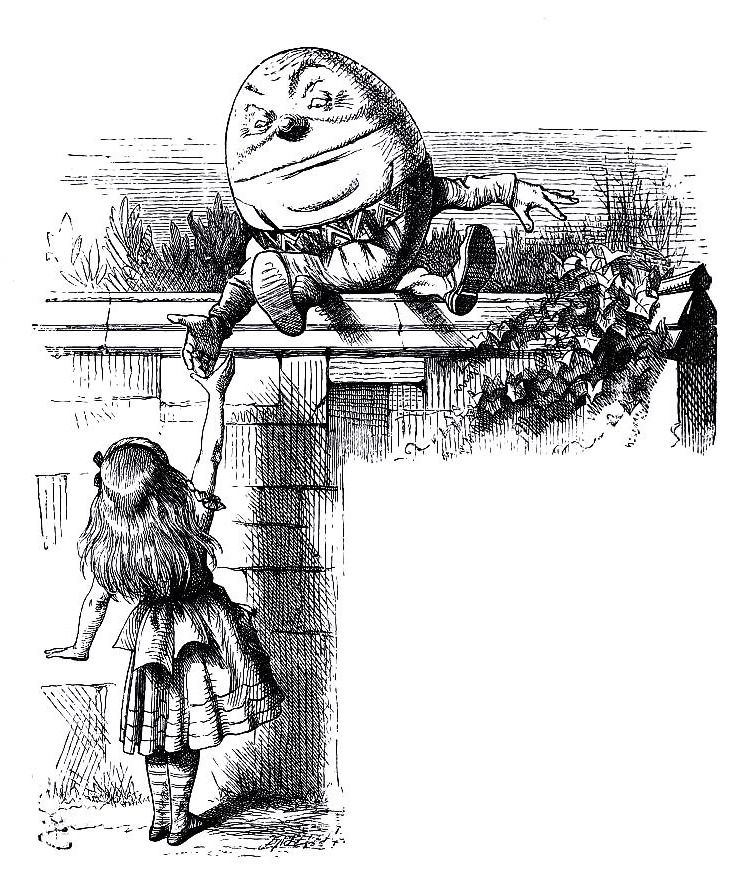

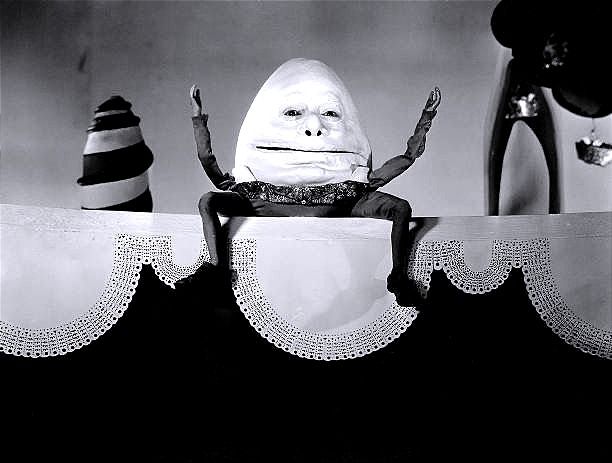

Humpty Dumpty

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

W.C. Fields

Pinterest.com

In the upside-down world of Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty is not just a nursery rhyme character: he is an arrogant philosopher, a twisted linguist, an anthropomorphic egg who believes himself wiser than everyone. Alice meets him sitting on a wall, poised between logic and delirium. Tenniel draws him as an egg dressed as a bourgeois, with his hands behind his back and the look of a tired professor. He is the one who explains to Alice the meaning of words like "slithy" and "mimsy", with a confidence that borders on madness.

W.C. Fields

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film, Humpty Dumpty not only appears, but does so with a memorable mask: he is played by W.C. Fields, a comic actor with a nasal voice and corrosive irony. His presence is a small masterpiece of casting: Fields, with his gruff tone and face hidden under a giant egg mask, transforms Humpty into a grotesque and irresistible creature, who speaks of "non-birthdays" and moves as if he were always on the verge of rolling away.

The scene is short, but intense. Alice looks at him with curiosity, he responds with superiority. There is no wall, but there is that same feeling of instability, as if every word could make it fall. The film does not faithfully reproduce the dialogue of the book, but retains its linguistic spirit and the tone of a walking paradox.

And even if the Carreras figurines do not depict him because, as we know, they are limited to the first book, his presence in the film is a declaration of intent: nonsense has no boundaries, and Humpty Dumpty is too iconic to stay out. It is the egg that cannot be ignored, even if no one will ever be able to put it back together.

The Knight who falls in beauty

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Gary Cooper as the White Knight (1933)

"Courtesy of the site doctormacro.com"

In Carroll's book, Alice meets the White Knight at the end of his journey between the squares of the chessboard. He is a sweet character, a funny and distracted inventor, who constantly falls from the horse but always gets up with a new idea: a sprung helmet, a lunch box attached to his leg. Tenniel describes him as a kind, almost funny man, with a slightly lost look and an uncertain posture.

Gary Cooper

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film, the Knight comes to life thanks to Gary Cooper, an actor symbol of American heroism, here transfigured into a fragile and dreamy hero. It is perhaps the most lyrical moment of the entire adaptation: Cooper appears on a screen crowded with masks and grotesque creatures, but manages to retain a visual tenderness that distinguishes him from all the other characters. It is not burlesque, it is not caricatured: it is poetic.

The costume faithful to Tenniel's boards is a wobbly armor, with sculpted details as if they had been assembled by a child playing with a tin. The helmet is too wide, the saddle too high, but Cooper never seeks realism: he points to the melancholic spirit of the Knight, who pursues Alice not to conquer, but to protect as a surreal father figure, born from a cultured sleep.

The scene is slow, intimate. Alice listens to him while he tells her about his useless inventions, his clumsy falls, his misunderstood poems. And here the film does not betray the text: it retains its fading dreamlike rhythm, the gaze that does not seek the comic but the evocative.

The Red Queen

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Edna May Oliver

Pinterest.com

In the mirror realm, where the squares are worlds and the characters move like pawns, the Red Queen rules without hesitation. It is not the Queen of Hearts of the first book who screams "Cut off her head!" with arbitrary hysteria but a sovereign of a completely different kind: cold, calculating, always on the move. In the 1871 novel, Carroll describes her as a figure who never stops running, engaged in an eternal paradox: "Here, to stay where you are, you must run as fast as you can."

John Tenniel illustrates it with almost geometric precision: severe face, checkered dress, posture as rigid as a diagonal. She is a queen of the chessboard, not of the heart, and her every gesture seems a strategic move, not an emotional explosion. Alice runs next to her, trying to keep up with her, but it is clear from the start: the Red Queen is time that accelerates, it is the logic that admits no respite.

Edna May Oliver

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 Paramount film, this complex figure takes shape thanks to Edna May Oliver, an actress with an unmistakable severe, sharp, theatrical profile. Her costume is sumptuous but square, her gait proud, her gaze sharp. He never laughs. He doesn't scream. But he commands nonsense with a surgical tone. Her presence in the film alongside the White Queen, in a strange balance between the first and second books is another proof of the intelligent chaos of the adaptation. There is no philological fidelity, but there is a visual power that nails the viewer.

THE WHITE QUEEN

The Queen Who Lives Backwards

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Charlotte Henry e Louise Fazenda

IMBD.com

In Carroll's second book, Through the Looking Glass, Alice meets the White Queen in a landscape that seems to have come out of a sleeping mind. She is a gentle sovereign, but completely disconnected from logic: she lives time in reverse, forgets facts before they happen, cries before pain occurs. Carroll builds her as a dream figure: she does not command, she does not explode, but oscillates in the void, with whispered words that seem to come from a forgotten diary.

John Tenniel draws her with a sumptuous dress and a bewildered face: she is diaphanous, delicate, almost evanescent. She is the queen that Alice could have as a grandmother, or as a future version of herself: wise and confused, strange and tender.

In the 1933 film, the White Queen comes to life through the interpretation of Louise Fazenda, a comic actress with an expressive face and theatrical movements. His costume is pompous and trembling, his bearing undulating. Fazenda does not act, he slips into the role. There is no authority in his gaze, but a strange innocence that makes the nonsense even deeper.

Alice has finally reached the eighth spot. Her promotion to Queen is official but in the mirror world, nothing happens as it should. The ceremony begins. Seated next to her, the White Queen and the Red Queen, both crowned, make up a royal trio that seems to have come out of a visual paradox.

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Tenniel draws all three with crowns on their heads: Alice in the center, the two Queens on the sides severe and trembling, opposite and complementary. But the tone is not triumphant: it is quietly delirious. The queens speak in a disjointed way, confuse the dishes of the banquet, make bizarre comments. And then, as if the ceremony were too intense even for them, the miracle of nonsense happens: The two sovereigns fall asleep, one next to the other, leaving Alice and the reader in the surreal silence that precedes the fade.

This scene is the heart of the book, where Carroll unmasks the meaning of the whole adventure: nothing really makes sense, yet every moment is full of meaning.

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Charlotte Henry, Louise Fazenda e Edna May Oliver

Pinterest.com

In the 1933 film, the royal trio comes to life with actresses Charlotte Henry (Alice), Louise Fazenda (White Queen) and Edna May Oliver (Red Queen): in a dreamlike and theatrical sequence, in a crowned circle of nonsense. This is precisely the absurd genius of the '33 film: even when it stages a royal ceremony, it does so under the effect of a bizarre dream, where the queens collapse like tired puppets, leaving Alice at the center, and us spectators in doubt whether everything is real or already vanished.

The King who doesn't know why he's King

John Tenniel`s original (1871) illustration for Lewis Carroll`s "Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There"

Pinterest.com

Charlotte Henry, Ford Sterling e Edna May Oliver

Pinterest.com

In the mirror realm, the White King does not reign. Cares. He is the husband of the White Queen, and in Carroll's book he is a secondary figure, but full of comic and delicate nuances: bearded, trembling, perplexed, often chased by his own messenger. He does not give orders, he does not impose himself. He lives as a pawn who has lost his sense of play, a figure who always seems to ask himself: "What move should I make, if I don't know where the board is?"

John Tenniel describes him as a kind old man, with a wrinkled face and a bewildered look. It is the perfect complement to the White Queen: two sovereigns who do not dominate, but slip into dreams, like wandering souls under a crown that is too light.

Charlotte Henry e Ford Sterling

Pinterest.com